Graphic Design in the White Cube

Essay accompanying the exhibition Graphic Design in the White Cube during the 22nd International Biennale of Graphic Design Brno 2006. Nineteen designers and collectives were commissioned to design posters for the design exhibition in which they were to participate. Instead of bringing work from the outside to the gallery, the work is made for the gallery. Instead of recreating the context for the exhibition, gallery conditions are the context for the work.

Organizing graphic design exhibitions is always problematic: graphic design does not exist in a vacuum, and the walls of the exhibition space effectively isolate the work of design from the real world. Placing a book, a music album, or a poster in a gallery removes it from the cultural, commercial, and historical context without which the work cannot be understood. The entire raison d’être of the work is lost as a side effect of losing the context of the work, and the result is frozen appearance stripped of meaning, liveliness and dynamism of use. Presenting design in an exhibition space in this way is akin to looking at a collection of stuffed birds in order to study how they fly and sing. In spite of this, it is more and more common to see design as ‘object’, not only in books and magazines, but also in the ‘white cube’1 of the exhibition space. Graphic designers struggled for a long time for recognition and professionalization of their field, and exhibits are considered one way of promoting the trade aspect of design. Everyone is happy: the designer whose work was selected by the institution; the original client who received an admired and acclaimed design, and the gallery which acquires the work to be presented. Work designed for a completely different purpose is recycled, and re-presented in a foreign environment. The same scenario is even more common in design publishing, and nearly instant books full of vague collections of work with little or no commentary take up increasingly more space on designers’ shelves, crowding out other books which are more laborious to research, write and publish.

A more recent trend is design which refuses to be seen only as an object of consumerism but draws parallels with art, reflecting the autonomy of the designer in his work, as well as a willingness to initiate projects himself. This generation of designers is not the first one that doesn’t rely solely on clients to come up with project briefs. Renowned Dutch designer Karel Martens, who taught some of the designers represented in this exhibition, has done uncommissioned, artistic work apart from his design career. Building on the tradition of the experimental printing of fellow designers such as Hendrik Nicolaas Werkman or Willem Sandberg, Martens’ prints and collages were done in his spare time as studies and experiments which fueled his other, more practical design work. Some designers today however integrate self-initiated work into their daily practice, no longer distinguishing between projects done in and outside of their working hours. Self-initiated work in graphic design is becoming increasingly more important for designers, starting up projects which probably would otherwise never see the light of day. The group of people who work in this way is still marginal, and it is no surprise that most of them live in countries with prosperous economies, occasionally receiving cultural funding to facilitate their unconventional approach to their work.

Graphic design has for a long time been defined as a service of a designer for a client, rooted in external impulses rather than internal ones. Design work done without a client hangs in a limbo between art and design. Graphic design is a fairly young profession, and as such still in a state of development. It is expanding to encompass various activities: writing, organizing, conceptualizing, reflecting. This is no longer design which is only defined by business cards and logos. Here we come to a problem of definition: until now I have been using the term graphic design with the assumption that everyone knows what it means. Especially in the context of the 22nd International Biennale of Graphic Design Brno with its 43 years of history, people have created expectations of what a typical graphic design exhibition might include. Let us understand ‘graphic design’ then, to mean a field in flux which is as flexible as the work that it embraces. Unlike the work of other professionals, the work of a designer is not restricted or defined by its content; in fact designers are trained to accommodate and express various, often contradicting ideas. It is a ghost discipline as Stuart Bailey writes: ‘…graphic design only exists when other subjects exist first. It isn’t an a priori discipline, but a ghost; both a grey area and a meeting point…’ Bailey calls attention to an area that many designers struggle with: the way that they refer to their activity in their field transcends the established notion of its definition. Designers represented in the exhibition Graphic Design in the White Cube move fluently between the worlds of art, design, music, theatre and writing. ‘I and everyone I work with just think of what we do as merely “work”. I studied typography and graphic design—that’s my background and it informs what I do—but now I do a variety of work, which may or may not come under those headings’, says Bailey in a recent interview. Others such as French designers M/M Paris2 directly challenge the definition of ‘graphic design’: ‘Graphic design could embody a lot of activities, and the definition is not fixed, but continually evolving. Because it is still a new profession, the best graphic designers are the ones who reinvent their field and surprise.’ Members of Amsterdam-based design studio Experimental Jetset say that limited notion of design is a misunderstanding: ‘Personally, we situate the birth of modern graphic design somewhere roughly between Marinetti’s Futurist manifestos, Piet Zwart’s leaflets for the Dutch Cable Factory, and Kurt Schwitters’ Merz publications (to name some obvious examples). So in our understanding, graphic design has always been an area where very different elements are synthesized: art, politics, poetry, industry, etc.’ In their view, all the people invited to exhibit here are then part of this great tradition, and are ‘graphic designers in the traditional sense of the word’.

M/M, Bailey and Experimental Jetset are no strangers to the gallery world. M/M has held numerous solo exhibitions in prestigious art galleries and collaborated on major events (Venice Biennales). Bailey has directed theatre performances and more recently together with David Reinfurt (Dexter Sinister) is involved in organizing Manifesta 6, the European Biennial of Contemporary Art in Cyprus, where they set up a model of economic production, responsible for all publishing activities of the Manifesta 6 school. Jetset activities include solo exhibitions in galleries in London, Utrecht and Arnhem, and group shows in SFMOMA San Francisco, Kunsthal Rotterdam, or Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam amongst others.

In 2005, M/M were invited to Paris’ contemporary art museum Palais de Tokyo to exhibit their work next to major artworks of the late 20th century in an exhibition which featured works by a variety of artists including Joseph Kosuth, Jeff Koons, Maurizio Cattelan, Vanessa Beecroft, Takashi Murakami and Mike Kelley. The intentions of the exhibition was to explore how different contexts cause the same work to be read in different ways, blurring the boundaries between disciplines.

‘Graphic design’, because of its ubiquitous nature, makes a considerable impact on the visual culture that surrounds us, so it makes a lot of sense to study this influence and critically discuss the work in the context of other visual arts as well. When presented in a museum however, the exhibition should attempt more than just passive presentation in glass cases. The isolated work lacks any real information about the reasons and processes behind it. What needs to become evident is the explicit purpose of the work, to see things otherwise inaccessible, otherwise the visitor is better off going to any bookstore or strolling down a busy street to get first hand experience of and physical interaction with ‘graphic design’.

There have been some design exhibitions which attempt to deal with these issues. Rick Poynor recently organized a major retrospective of British graphic design entitled Communicate first held in London, now travelling world wide. The exhibition sets out to examine graphic design’s influence on contemporary culture, highlighting experimental work created by designers who aren’t limited by working to fulfill a commercial client’s brief. The exhibition occupied eight rooms of the Barbican Art Gallery, and Poynor, whose background is in journalism and publishing, organized these rooms as ‘chapters’ of a book, each section presenting a different aspect of work, with introductory texts explaining each section of the exhibition. The points and comparisons of the work were made through careful visual editing of the presented pieces.

Another example is the exhibition of Dutch graphic design that I was asked to organize a few years ago for the Brno Biennale. Given the fact that for practical reasons the work was to be displayed in a gallery space involving a certain degree of isolation of graphic design, the presentation attempted to clarify its function more, sketching out the triangle of client-designer-public. Since the work of the designer was brought to the gallery to be judged by the local public, the focus was on presenting the missing component, that is, providing space for the clients. The words of the commissioners in the formulation of the original brief were presented instead of the designer’s retrospective comments. The original brief illuminated the purpose of the work, while the public could evaluate how successfully it communicated.

However, a retrospective attempt to recreate the context for a work may not be the ultimate solution either and has its own pitfalls, as Experimental Jetset points out: ‘There’s also something false about it: trying to recreate “the outside world” inside a museum/gallery, as if the museum/gallery is not a valid context in itself. In our opinion, in these cases, we think that it’s best to underline the museum context as much as possible, to be brutally honest that the context in which the object is shown is totally different from the context the object was originally designed for.’

So it is in this context that we set to organize a ‘graphic design’ exhibition, with the intention of the commissioner, the Moravian Gallery in Brno, to ‘present to the public certain specific aspects and tendencies of contemporary graphic design worldwide’. Being extremely self-conscious, we propose a possibility: instead of bringing work from the outside to the gallery, let’s make the work for the gallery. Instead of recreating the context for the exhibits, let’s make the gallery conditions the context for the work. Nineteen3 designers and collectives were commissioned to design a poster for the design exhibition in which they participate. The posters will function on two levels: the collection of posters is to constitute the exhibition, and copies of the posters will be spread around the city to inform visitors about the exhibition. This is obviously a dangerous snake-eating-its-own-tail strategy, yet the self-referential nature of the brief makes it possible to illustrate otherwise invisible mechanics of the work process.

The usual conditions of design are created in the gallery: designers were directly commissioned to make the poster in four weeks’ time, were offered a (minimal) design fee, and were asked to treat the commission just like any other projects they work on. What is perhaps unusual about the exhibition is that it makes some invisible components visible. The original brief of the project is dominantly presented in the exhibition, as are all sketches that the designers made. The objective is not to lionize the work, or create easy material for value judgment, but to uncover the process of work, presenting all the sketches that designers made, including those not leading anywhere. Failures can provide more information about visual art than just a presentation of its successes.

The focus on itself, the self-referential nature of the project is certainly not new. It has been explored in fine art for a long time, one famous example being René Magritte’s seeming contradiction Ceci n’est pas une pipe, which questions the representation of objects in art. In the 1960s, Sol LeWitt and other conceptual artists worked on reducing the artistic process to its bare elements. Four Basic Kinds of Lines & Colour, is a book project investigating basic book printing techniques. Using standard CMYK colours, LeWitt drew lines at 0, 45, 90 and 135 degree angles following the standard angles of reproduction techniques. Starting with four inks, he was able to mix 16 elementary colours, and using different densities of the black ink, also 16 grayscale equivalents.

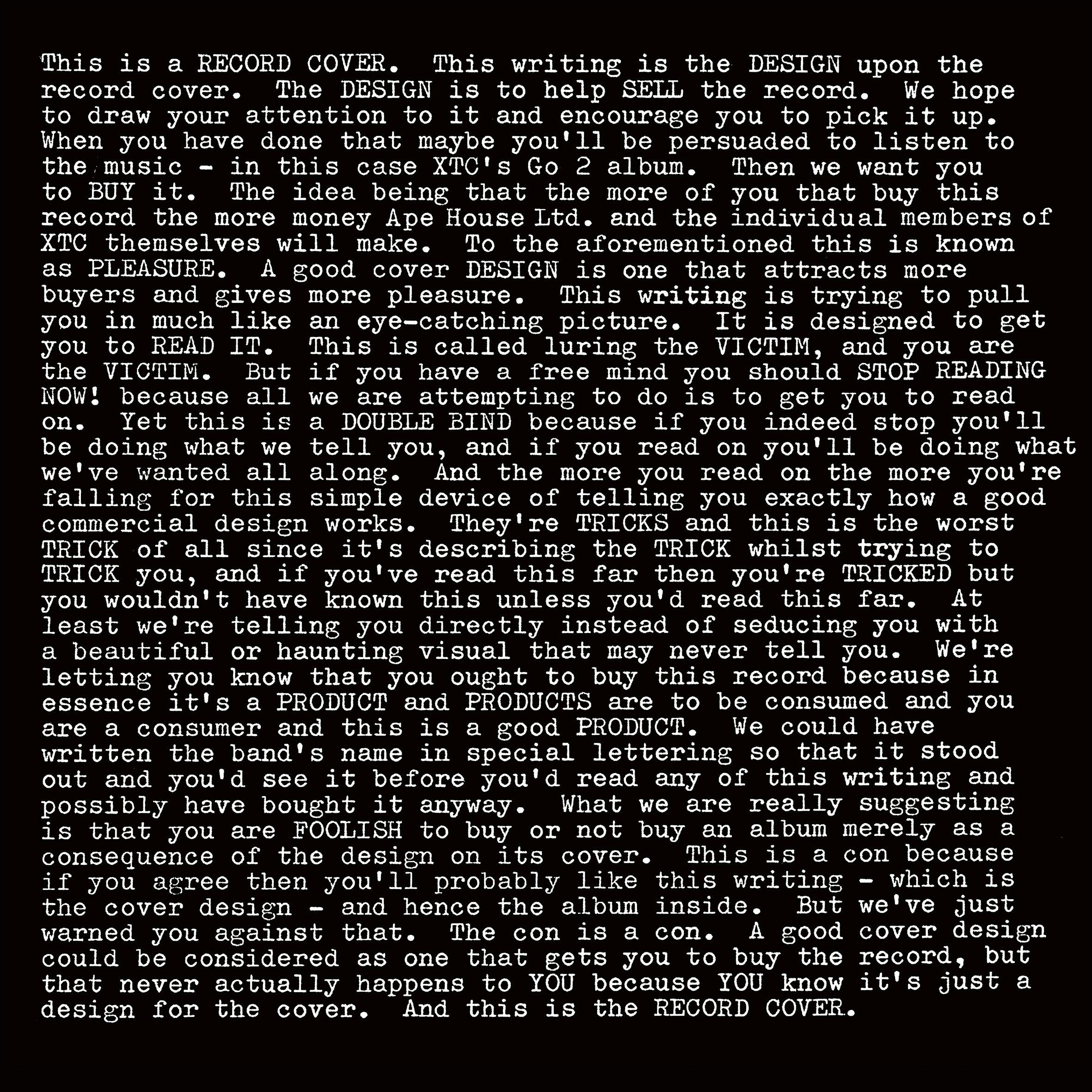

One of the most brilliant self-referential works of design is XTC’s album Go 2 (1978) designed by British art design group Hipgnosis which exposes the mechanics of marketing persuasion, blatantly including them in the design. The cover of the album reads: ‘This is a RECORD COVER. This writing is the DESIGN upon the record cover. The DESIGN is to help to SELL the record. We hope to draw your attention to it and encourage you to pick it up. When you have done that maybe you’ll be persuaded to listen to the music – in this case XTC’s Go 2 album. Then we want you to BUY it. The idea being that the more of you that you buy this record the more money Virgin Record, the manager Ian Reid and XTC themselves will make. […]’ The text goes on to call the buyer a victim, explaining the tricks of marketing, suggesting that it is foolish to buy a product based on the design of the cover.

Our strategy for the exhibition was to strip the design process of its deceptive aura, propose a possible format for design exhibitions, and yet present everything that a visitor to a ‘graphic design’ show might expect.