Tracing Meitei Mayek & Ol Chiki Letters: A Comparative Study

This essay explores socio-linguistic landscape of northeast of India and adoption of two minority writing scripts, Meitei Mayek and Ol Chiki, enjoying significant growth in popularity in recent years, establishing distinct identity of their users.

India’s linguistic landscape is characterised by a great degree of graphic diversity, with a wide range of scripts in active use across the country. Some of them, like Devanagari, are used to write many languages, while others, such as Malayalam, are almost exclusively used for one language. Then, adding to this mix, are languages written in multiple scripts.

Most of India’s major scripts are descended from the ancient Brahmic script, and reflect ancient phonetic ordering, as well as complex script behaviour, with vowel markers combining with consonants, and conjuncts representing consonant clusters. Descendants of the Brahmic script are used across modern India and Southeast Asia, and they possess a certain graphic and orthographic cohesion.

However, common in modern India is the sense that a language must have a unique script to represent it, in order for the language to have a distinct identity. In other words, a unique graphic identity is linked to a distinct linguistic identity.

The technological and commercial forces of 20th-century print culture helped consolidate the association of literary languages with particular scripts. At the same time, emerging notions of linguistic nationalism tied script to linguistic identity, casting scripts as markers of identity that carried with them centuries of literary history. Intellectuals documented and examined examples of pre-print writing, especially inscriptions, to establish the antiquity of India’s linguistic communities.

After Indian Independence (in 1947), linguistic nationalism expressed itself in the form of linguistic states within the Indian union, where language communities claimed geographic territory as their homeland and demanded that the respective states represent them and their languages. In 1956, these demands were finally heeded, and India was administratively re-organised along linguistic lines, with each linguistic state promoting its own language.

However, India’s smaller, less prominent languages missed out on these developments. These linguistic communities were not part of the original wave of linguistic nationalist movements, and they have taken longer to assert their identity and develop their written forms. Many of these languages use scripts that sit on the margins of India’s linguistic landscape, with some of them unrelated to the Brahmic scripts that dominate elsewhere.

In this essay, we look at two such scripts that have seen a growth in popular usage, in more detail: Meitei Mayek and Ol Chiki, used to write Meitei and Santali respectively. There are many such scripts, but these are among the most widely used. Importantly, both Meitei and Santali are among the 22 languages recognised by the 8th Schedule of the Constitution of India. Meitei was added in 1992 (as ‘Manipuri’), and Santali in 2003.

Meitei and Santali are currently written in multiple scripts. In India’s vast linguistic landscape, where most major and Scheduled languages have invariably settled on one script, Meitei and Santali stand out as anomalies.

Crucially, both languages also use individual scripts unique to them, seen in no other linguistic community. In addition, each of the language communities have suffered numerous forms of cultural, technological and political neglect.

Meitei Mayek and Ol Chiki are disparate scripts used for unrelated languages in very different settings. The dynamics of their usage, as well as user preferences, are dictated by a complex set of sociolinguistic and political factors that reflect the way the languages themselves are continuing to develop. A closer examination of these forces offers insights into the processes of script development and adoption in India.

Social status

Meitei and Santali are not as widely used for writing as most of India’s other Scheduled languages, although Meitei does have a long literary history, including patronage by local kings and, in modern times, an active print sphere. However, Manipur is still a small state, and its literary culture is not as robust as that of other states with larger language communities. Manipur, like the rest of northeast India, is economically and culturally neglected by the Indian mainstream and the government. While Meitei speakers are dominant in their own state, they wield little influence nationally.

Santali on the other hand does not have a long history of writing, and the geographical dispersal of the Santal community has made script unity and literary circulation challenging. Santali speakers are classified as adivasis (indigenous), and have been subject to discrimination and exclusion from broader Indian society for many centuries, a legacy that persists today. Santal culture and lifestyles, along with those of other adivasi communities, have been neglected by the Indian state, with members of the community continuing to face economic disadvantages.

Graphic variation

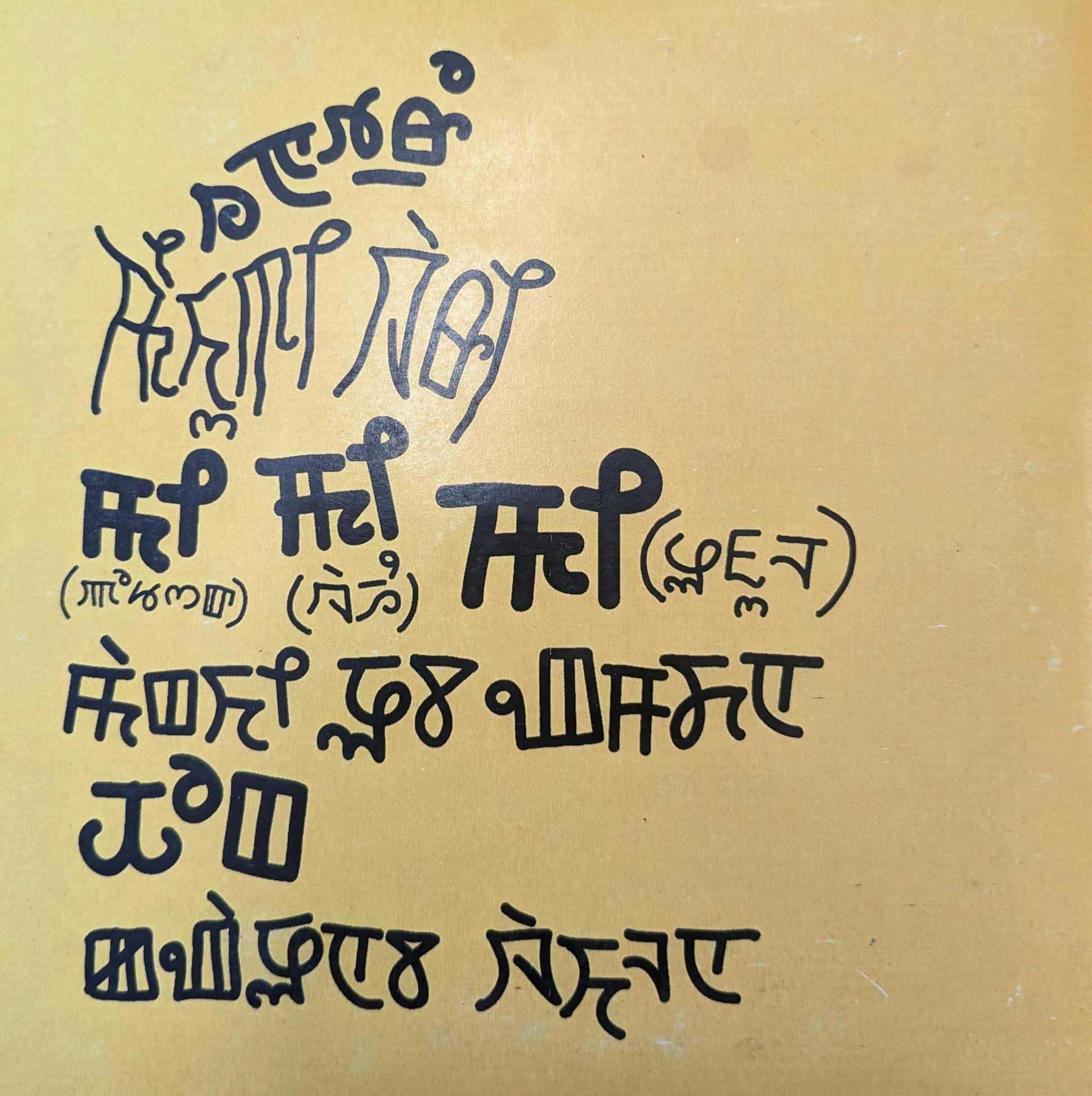

Both scripts have limited graphic variation, reflecting their lower degree of active usage. Meitei Mayek has more reference points for stylistic variation, thanks to its history of pre-print examples in manuscripts and inscriptions. In the years following its public promotion, signage artists have experimented with different lettering styles, especially in terms of stroke weight and letter proportions. Certain styles also feature manuscript-esque flourishes, although fonts do not generally reflect this diversity.

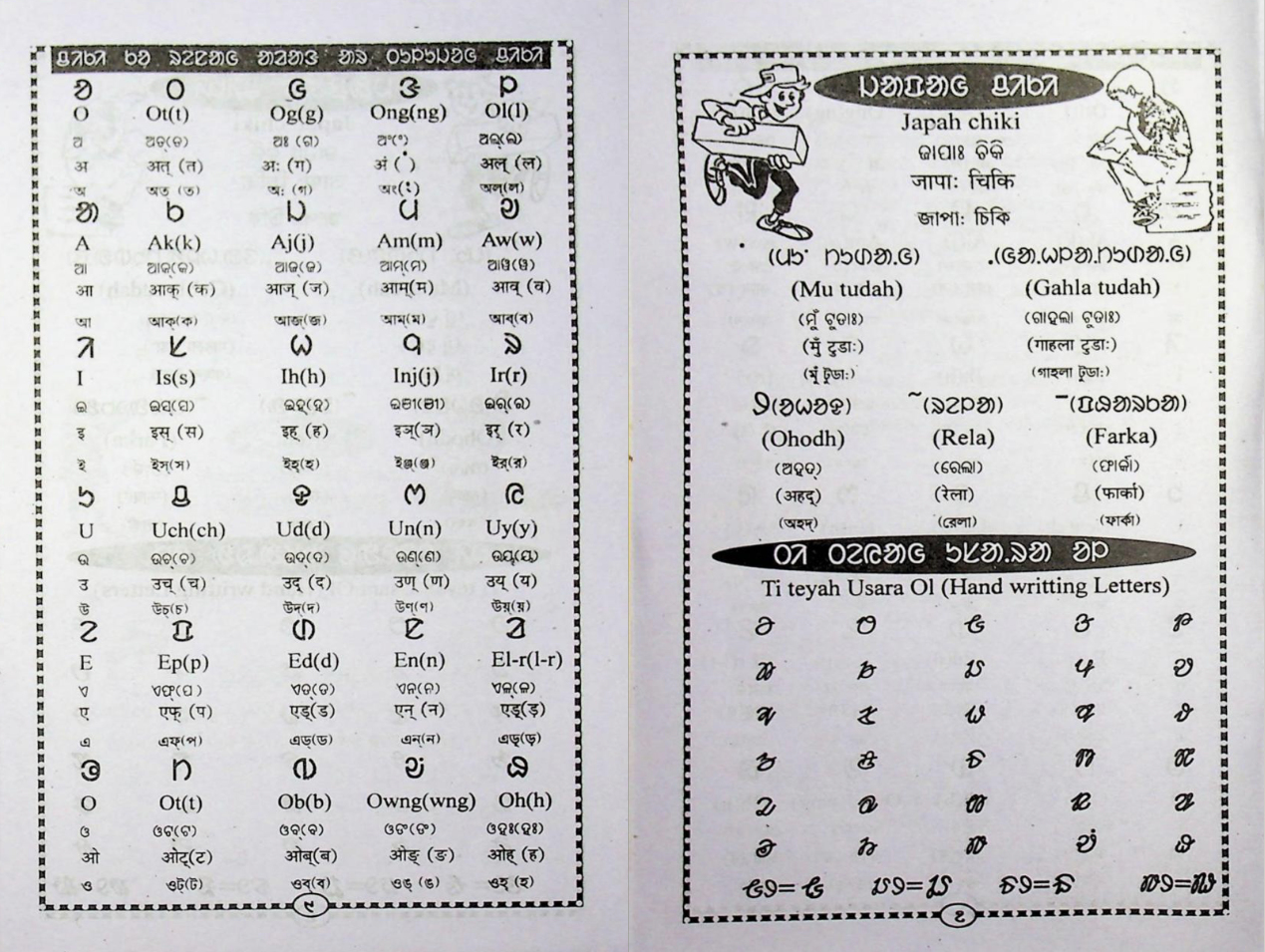

Ol Chiki styles are more limited. The two main styles are the blockier print (chapa), and a more flowing, almost cursive handwritten style (usara). The latter has even been reinterpreted as lower-case letters by some writers, but this is not widely accepted. In interviews, Santali speakers shared with us their desire to see more stylistic variation in Ol Chiki, to make it more aesthetically pleasing and attractive. So far, the existing fonts do not allow for much variety in the script.

Script complexity

Unlike the Brahmic scripts, Meitei Mayek and Ol Chiki are relatively simple. Both are written from left to right, and are unicameral.

Meitei Mayek still functions as an abugida. Vowel diacritics are combined with consonant letters: below them, to their right, above them, and to their left. Tone is sometimes indicated through vowel markings. There are no conjunct consonant forms in the standard character set, and each letter is named after a body part beginning with the phoneme the letter represents, such as ꯀ kok (‘head’) and ꯃ mit (‘eye’).

Ol Chiki is an alphabet, which is fairly rare in India. Each letter corresponds to a phoneme, and some letters represent a different phoneme at the end of words. Certain letters modify the pronunciation of preceding letters, but they do not combine with them. Each letter symbolises different shapes deriving from the traditional surroundings of Santals, such as ᱥ is, resembling a plough.

Inclusion on banknotes

Indian banknotes feature 15 Scheduled languages on the reverse, in addition to Hindi and English. However, neither Meitei nor Santali are among them.

Manipuri politicians have made calls to add Meitei (in Mayek) to Indian banknotes, alongside the other Scheduled languages featured, and Santali-speaking leaders have made similar calls, including MP Rama Chandra Hansdah, who raised the issue in the Indian Parliament, declaring that Santali in Ol Chiki deserved to figure on banknotes.

Phone support and typing

Most Indians use the internet via their mobile devices, and a greater proportion of the population own mobile phones than laptops. Digital language usage is primarily mediated through phone keyboards, whether on smartphones or feature phones.

In 2017, the Bureau of Indian Standards issued a mandate requiring all phones sold in India to carry support for all Scheduled Indian languages, with the same applying to keyboards for typing. This has ensured the presence of Ol Chiki and Meitei Mayek on phones, despite their small user base.

Around 95 per cent of smartphones in India run on Android, meaning that users typically engage with Noto Sans fonts for Meitei Mayek and Ol Chiki on their phones.

Typing in Meitei Mayek involves a learning curve. Native input keyboards are not entirely intuitive, and transliteration is often preferred. Typing in Ol Chiki is fairly simple, and various IMEs offer native input and transliteration options.

For both languages, a number of keyboards are available on the Google Play Store, in addition to in-built Google Keyboard support. These third-party apps tend to be more popular, and are generally community developed.

Meitei Mayek

Meitei Mayek, or the Manipuri script, is the indigenous script of the Manipuri or Meitei language (also Meiteilon). Meitei is a Tibeto-Burman language spoken by approximately 1.8 million people, mostly in Manipur, a state in India’s linguistically diverse northeast region. It is the state’s official language and the first language of ethnic Meiteis, as well as being spoken as a second language by local Naga and Kuki tribes in the state.

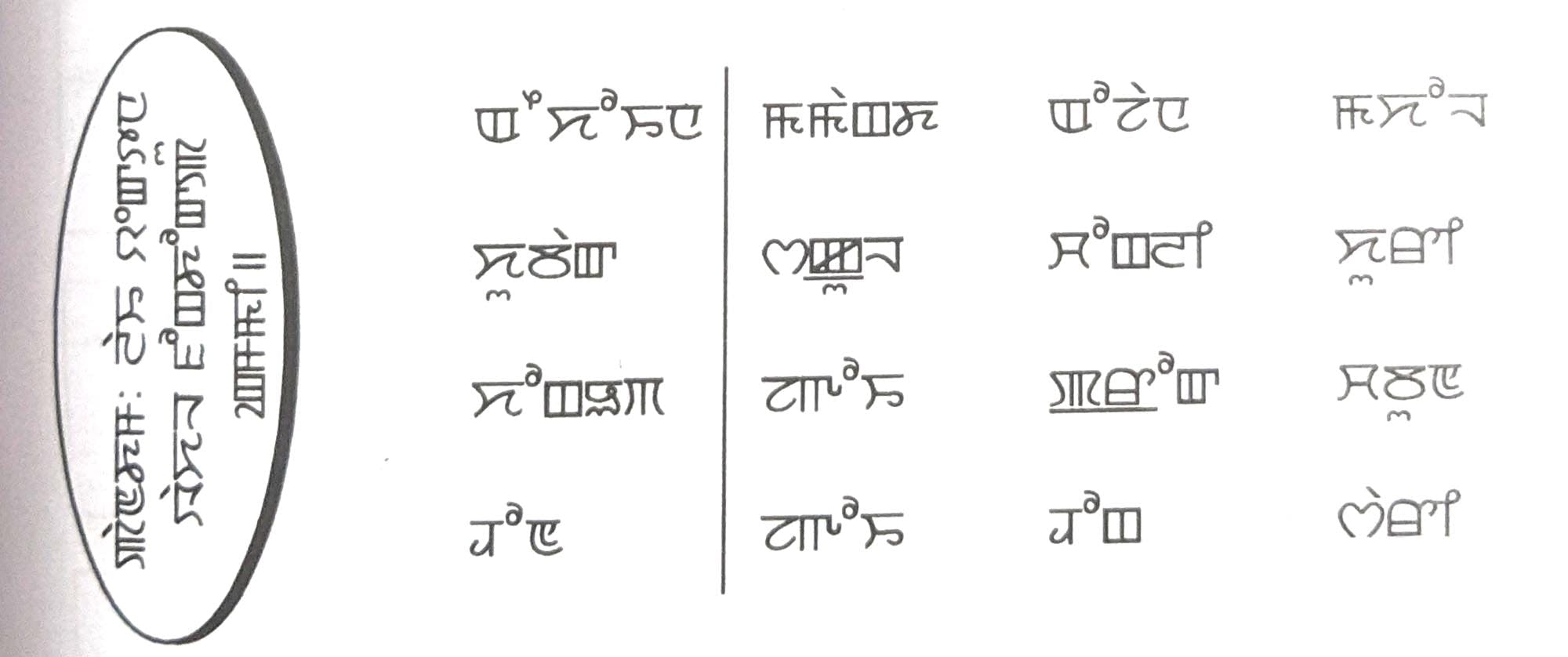

In contemporary Manipur, both Eastern Nagari (or the Bengali-Assamese script, simply ‘Bengali’ locally) and Meitei Mayek are used to write Meitei. However, each script is used in different sociolinguistic contexts, with different audiences.

Meitei Mayek is distantly related to the Tibetan script, and is recorded from the mid-11th century onwards. It was largely replaced by the Eastern Nagari script in the early 18th century, and had mostly fallen out of use until a mid-20th-century revival occurred, led by Manipuri intellectuals.

For close to two centuries, Eastern Nagari was the primary script used to write Meitei, well into the 21st century. Meitei Mayek was reconstructed in the mid 1900s and promoted by local cultural groups, but remained obscure and symbolic in popular usage for most of this period.

A sociopolitical preference for Meitei Mayek has persisted in Manipuri society, fuelling script revival efforts over the decades, especially from the 1970s onwards. These sentiments are strongly tied to assertions of a distinct Meitei identity, and script politics have followed the currents of local identity politics.

Origins and decline

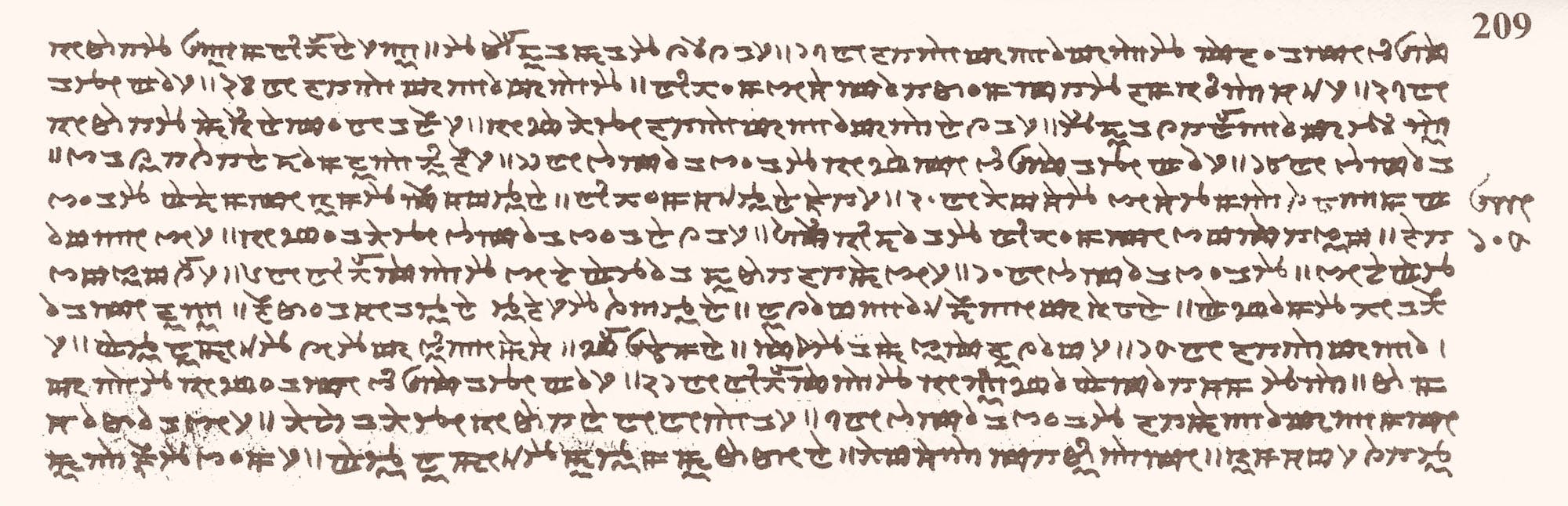

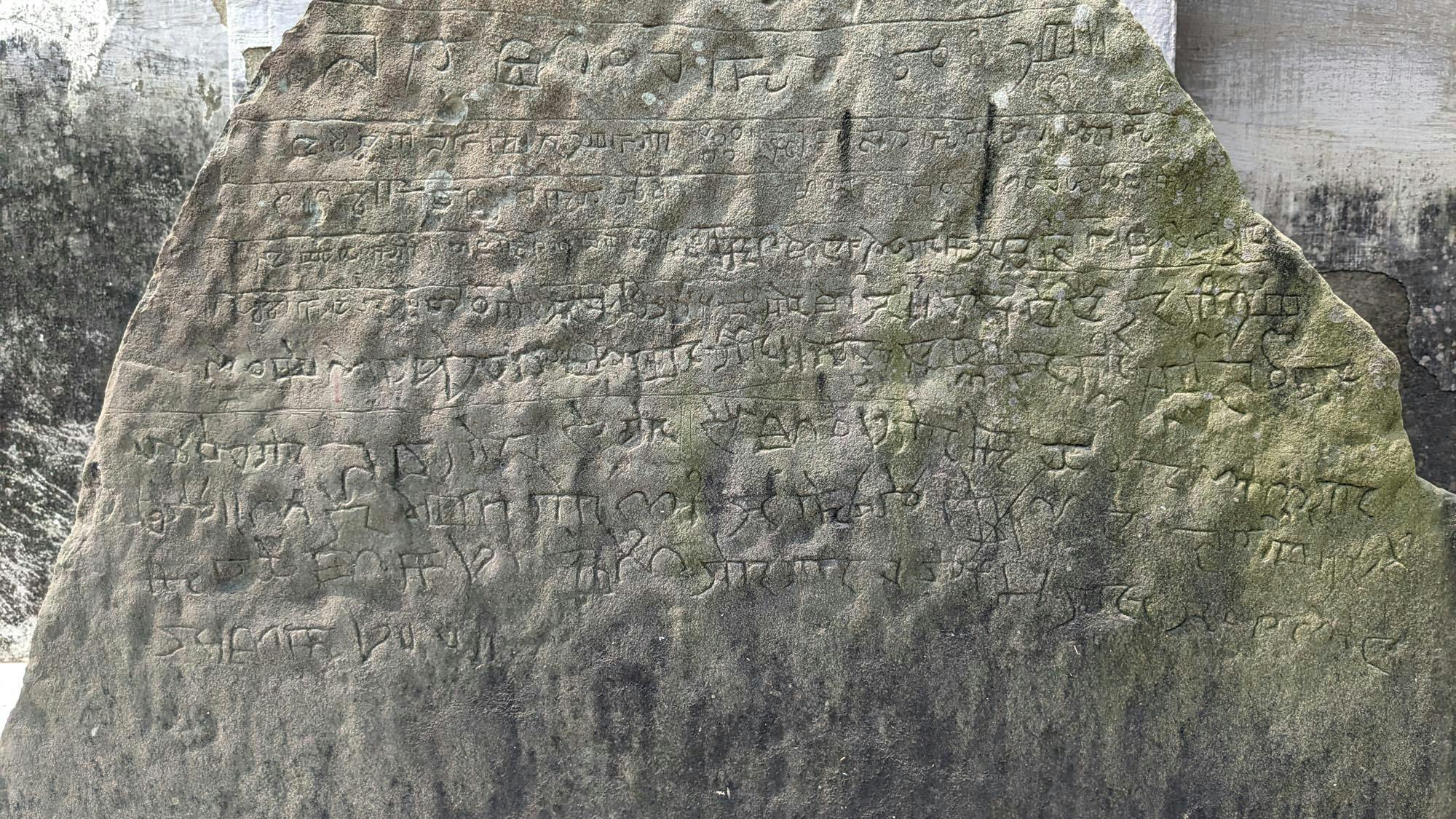

Before its decline, Meitei Mayek was widely used by local rulers, elites and scribes, with many inscriptions and at least 437 manuscripts from this period having survived.

The usage of Eastern Nagari to write Meitei is popularly tied to the king of Manipur’s conversion to the Vaishnava faith, and the influence of courtly and religious culture from neighbouring Bengali-speaking Sylhet.

In popular Manipuri consciousness, the decline of Meitei Mayek started when the local King Pamheiba (1720–51) burned traditional Meitei religious scriptures, or puyas, purportedly to extinguish their teachings. The puyas were written in Meitei Mayek, and the king is said to have imposed the script of the new Bengali faith on his subjects. Interviews with Manipuris, both intellectuals and laypeople, corroborate the extent to which this belief is held.

However, despite the almost mythical account of the burning of Meitei Mayek manuscripts, the script continued to be used in limited contexts after this event, well into the 1800s. For example, in 1868 the king of Manipur wrote a letter to the British viceroy of India in Meitei Mayek.

The epigraphy section at the Manipur State Museum hosts a small but significant collection of inscriptional and copperplate records written in Meitei Mayek. Most of the inscriptions date from after Pamheiba’s rule, including one from the late 1800s, showing that the script was still in active use, at least among the literate class of the time.

Historian Saroj Nalini Arambam Parratt writes, ‘It was only with the introduction of Western education from the end of the nineteenth century that the use of Meetei Mayek declined and became the prerogative of the maichous (scribes). Manipuris of the diaspora, trained in Bengali, also introduced Bengali script for the earliest printed books in the Manipuri language (from 1900). Meetei Mayek never fell out of use, though the rise of printing meant that all Manipuri material after 1900 came to be produced in the Bengali script.’

Eastern Nagari fonts were also widely available and used thanks to Bengali- and Assamese-language printing._ _While Meitei Mayek faced pressure from Eastern Nagari from the 1700s, the shift to the print medium sealed its decline.

Revival and standardisation

The 20th-century revival of Meitei Mayek went hand in hand with standardisation efforts, since the script had to be defined before it could be promoted.

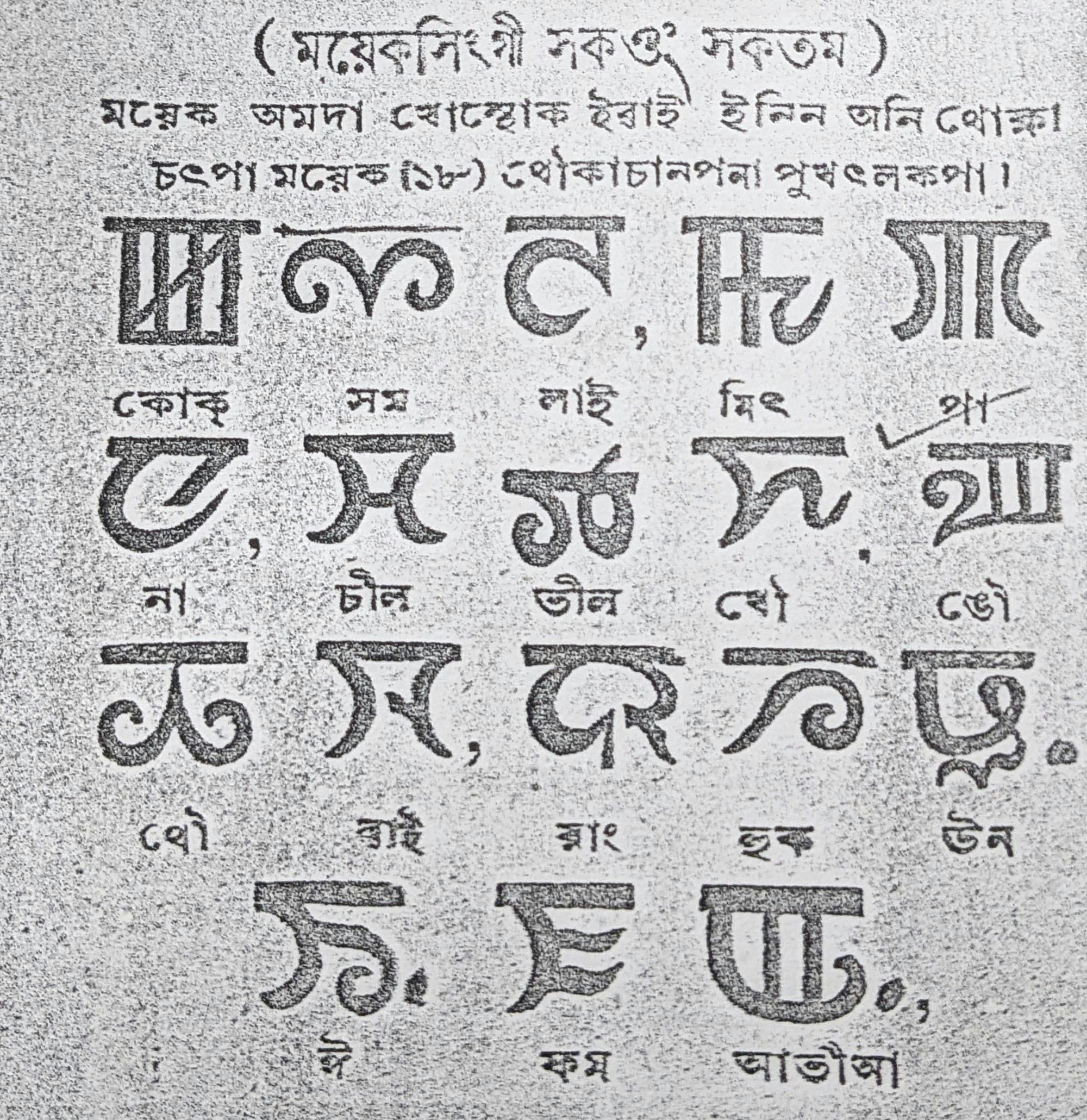

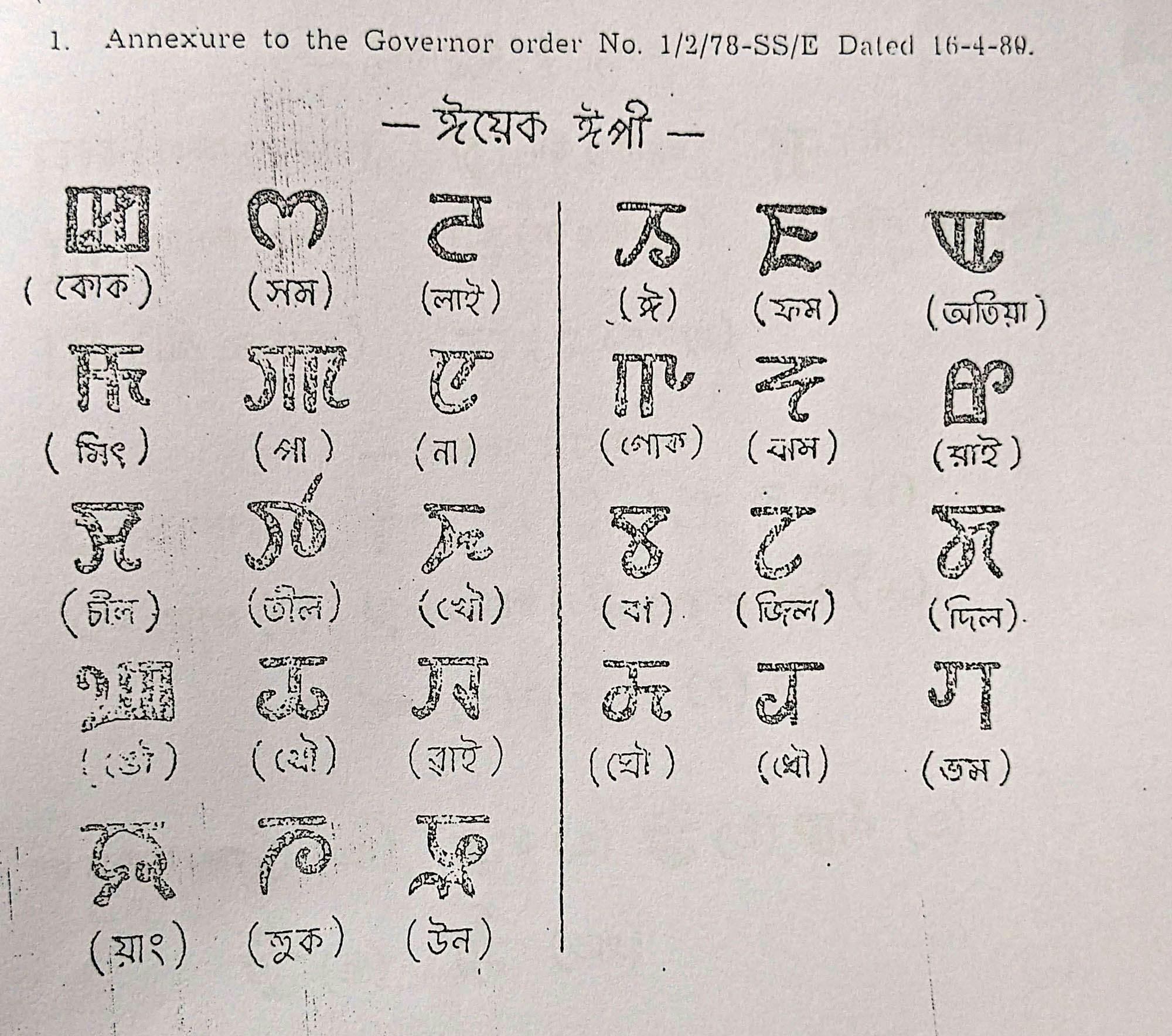

Meitei Mayek was standardised in 1978, by the government-organised Mayek Luptin Committee, consisting of local intellectuals and activists. However, this process had already started in 1962 with the Mayeki Conference, led by local activists. The Mayek Luptin Committee went on to recommend that Meitei Mayek be taught in schools, but this seems to have been ignored for practical reasons.

Old puyas and inscriptions were discovered and consulted in order to decide upon letterforms and script behaviour. Interestingly, those involved in both the committee and the conference consulted with elderly scribes to ascertain the letterforms used in puyas, indicating that knowledge of the script persisted in some quarters.

The official character set for Meitei Mayek contains five vowels and 22 consonants, with some unique final consonant forms. The number of letters in the script has also proven a source of controversy.

Some confusion came from the fact that Meitei had evolved over the centuries, and the range of Meitei Mayek samples reflected different stages and registers of the language. The oldest samples only had 18 letters, lacking sounds like r, d and dh.

On the other hand, certain samples reflect strong Bengali influence, featuring conjunct consonant forms and eight extra letters for Indo-Aryan phonemes, with a total of 35/36 letters.

The revival of Meitei Mayek is in some ways arguably more of a reconstruction, since it uses a curated form of the script to suit the technological and political needs of the modern age, instead of using the older pre-print script as is.

A local organisation dedicated to Meitei linguistic nationalism, MEELAL, has been proactive in promoting Meitei Mayek in civil society. Some of their actions have, however, involved violence, including arson of the Manipur State Library, housing Meitei books in the Bengali script.

Language and education policy

In 1979, the government of Manipur passed the Official Language Act, Manipur, designating Meiteilon or ‘Manipuri’ written in the Bengali script as the official language of the entire state.

Following local agitations and movements advocating for the promotion of Meitei and Meitei Mayek locally as a marker of Manipur’s unique and distinct culture, as well as proof of its antiquity, activists took to the corridors of New Delhi. In 1992, Manipuri was added to the 8th Schedule, giving it the seal of national recognition.

In 2005, Meitei Mayek (based on the government’s 1978 standard) was added to the local syllabus, and textbooks were changed from the Bengali script. This was done in phases – with each year, a new grade was taught Meitei Mayek, starting from the first grade. In 2015, the first HSLC exams (10th-grade finals) in Meitei Mayek were conducted, an important milestone. In 2022, the first batch of children to have learned Meitei Mayek in school started their master’s degrees.

In 2021, the Official Language Act, Manipur was amended to include Meitei Mayek as the primary script used for the language, with a provision for the Bengali script to also remain in use for another ten years.

Public presence

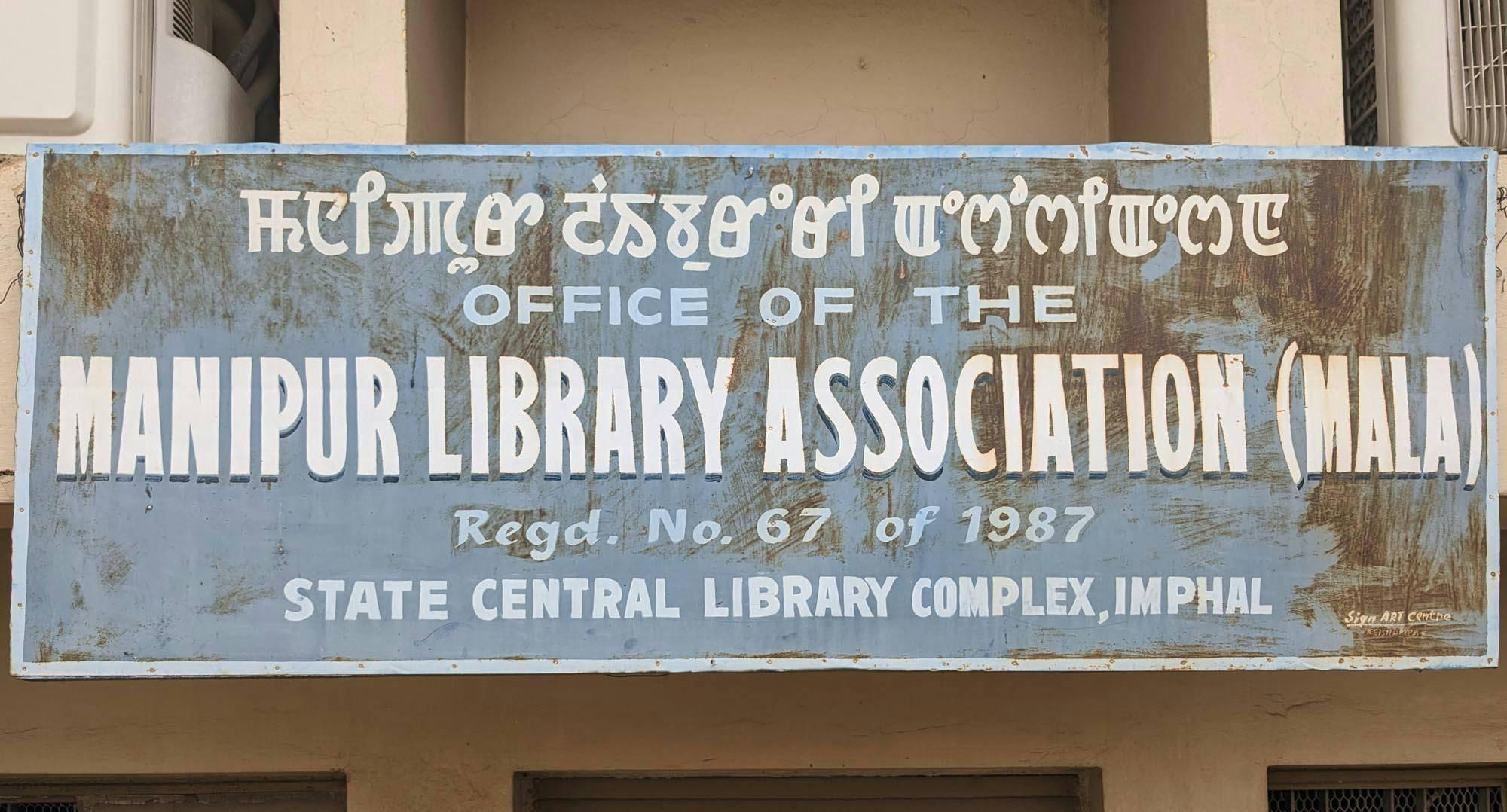

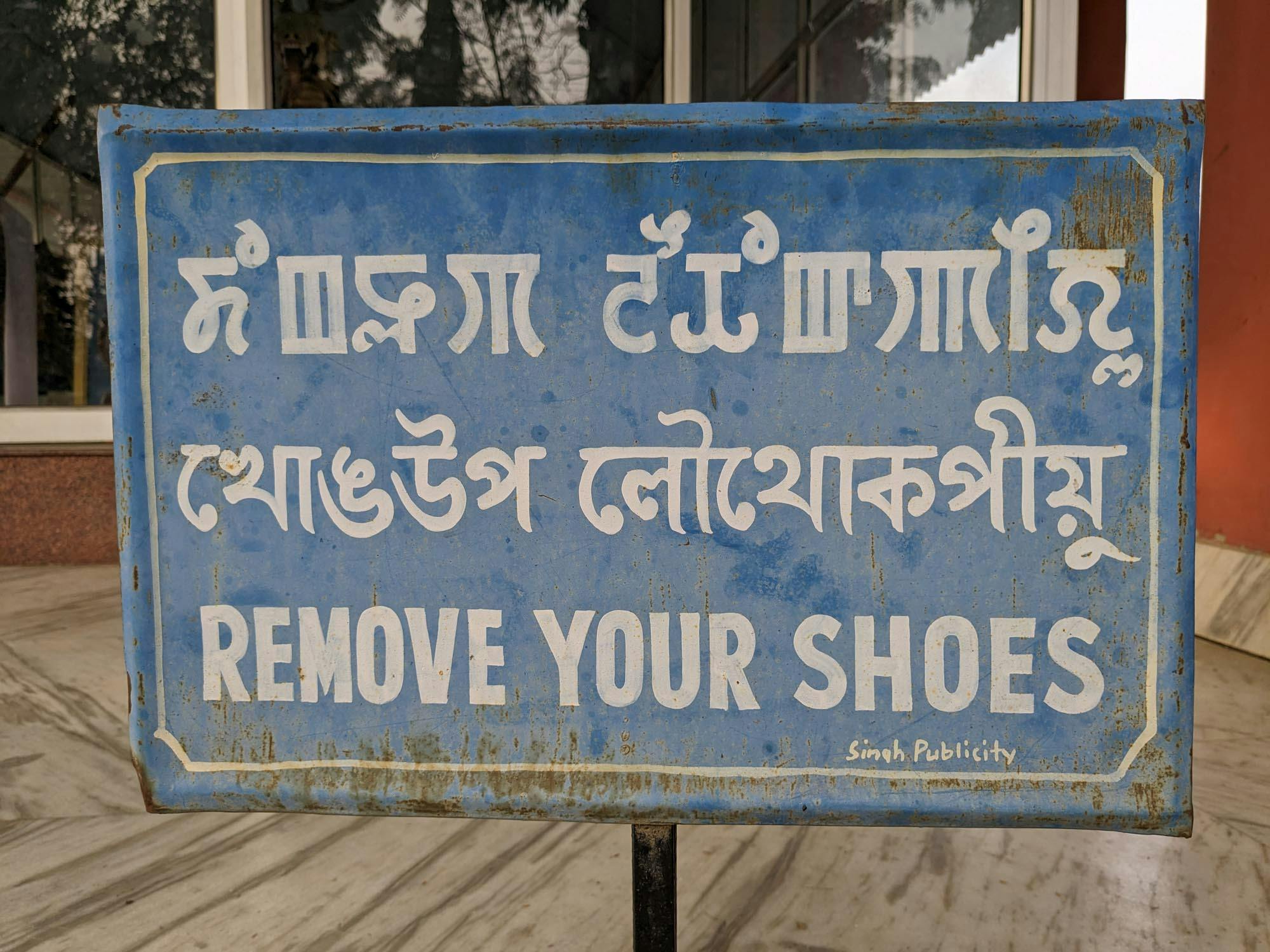

Over the last decade, Meitei Mayek signage was made mandatory for commercial establishments and government offices, decisively bringing it into the public sphere. Bengali script writing is no longer officially promoted; however, the reality on the ground is a lot more complex.

Most Manipuris cannot read Meitei Mayek yet, making public usage of the script largely symbolic. Signage usually carries English text as well, which serves as an alternative.

Bengali script writing persists in contexts where a message or important information is intended to be conveyed. Public announcements, health advisories (including for COVID-19), directions, and instructions in public spaces are written in both scripts, even if the title or heading alone is in Meitei Mayek. Thus, in situations where clear messaging takes precedence over symbolism, the Bengali script cannot be ignored.

Publishing

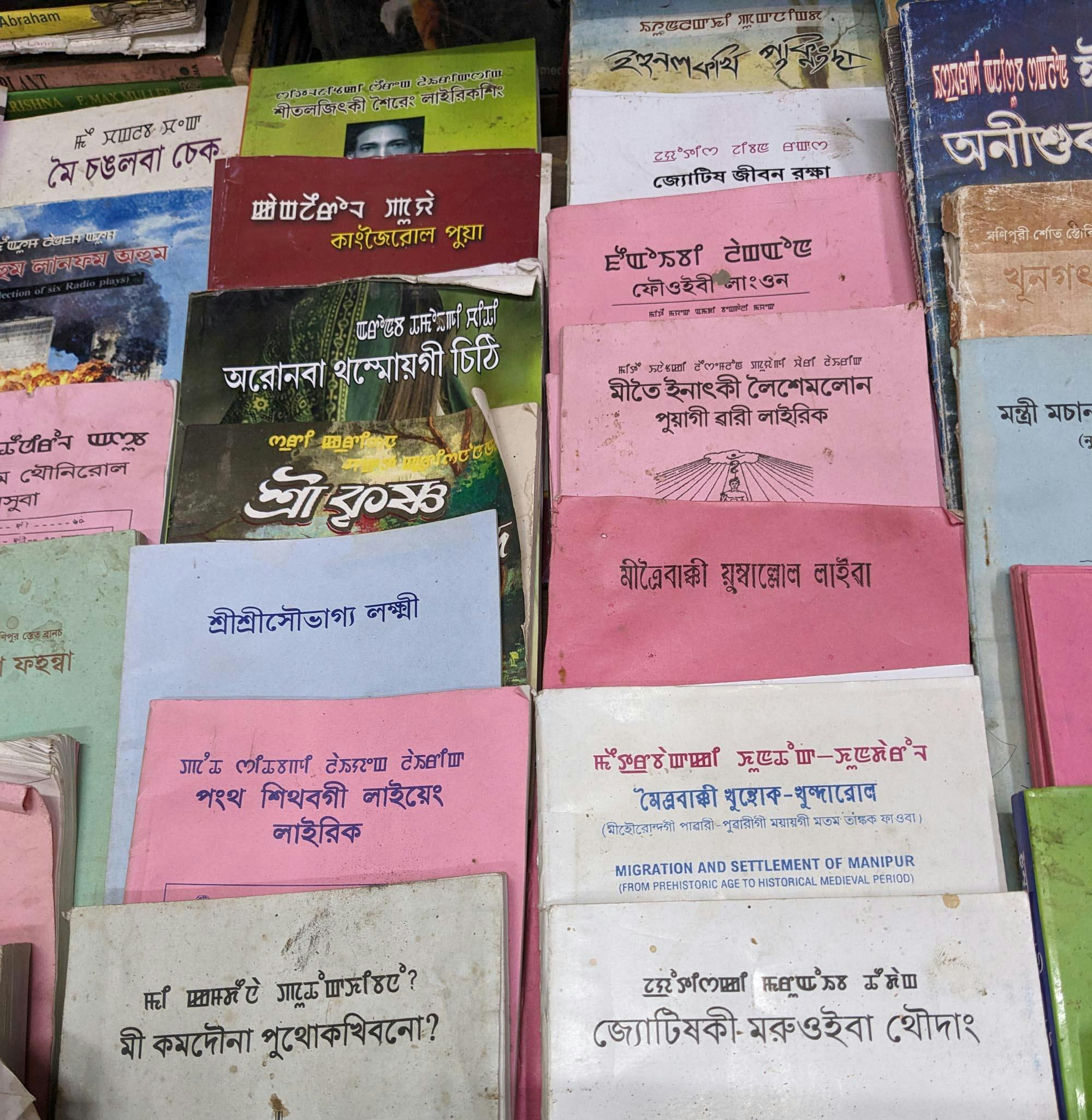

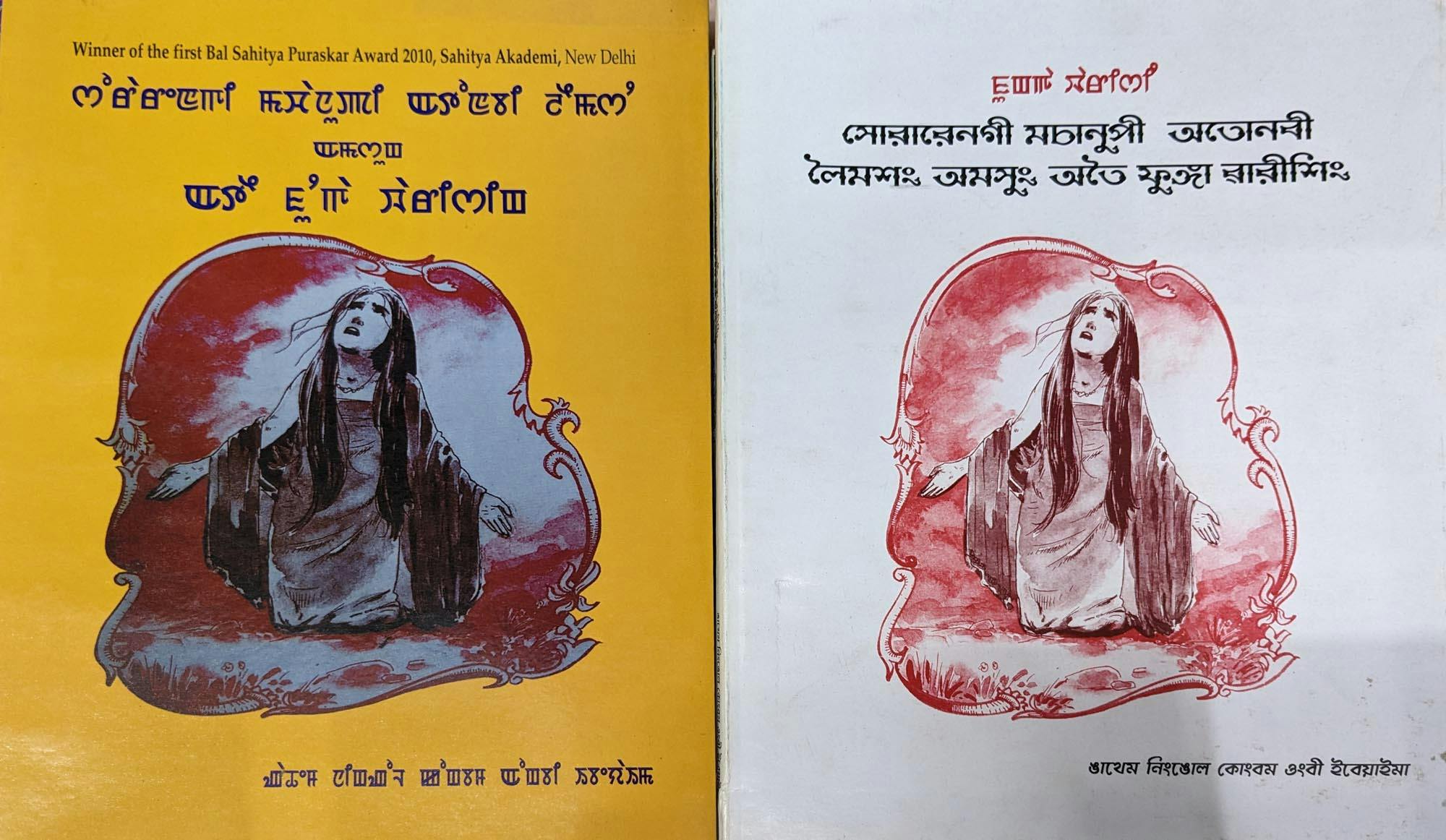

Visits to bookstores across Imphal have presented an interesting picture of graphical coexistence.

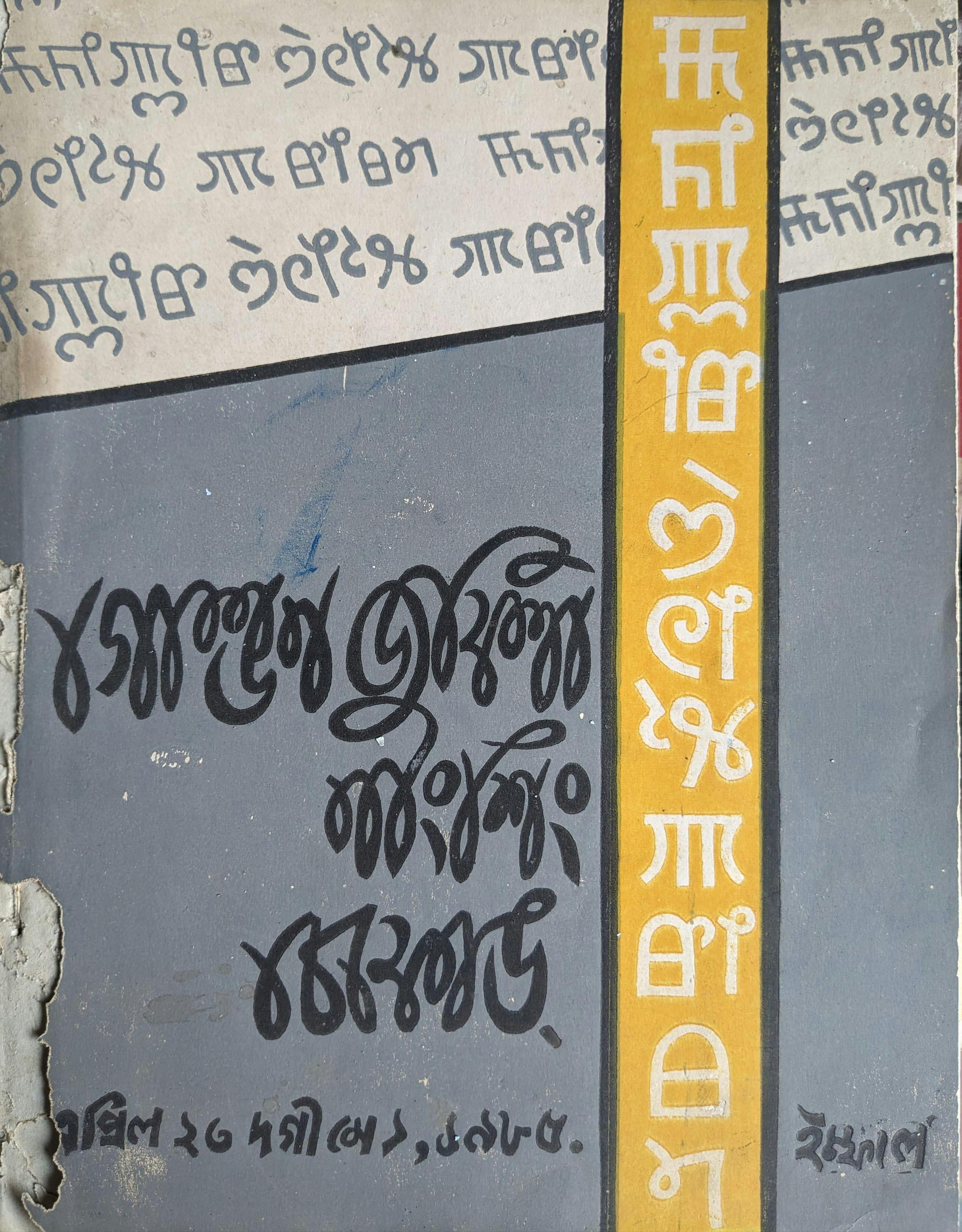

These shops stock books in the Bengali script, Meitei Mayek, and even combinations of both. Books published before 2000 are overwhelmingly in the Bengali script, but often use Meitei Mayek lettering on the cover. The lettering in this context serves a more symbolic purpose, indicating that the book is in Meitei or that it relates to local culture or identity.

Meitei Mayek publishing began to pick up, however, after fonts supporting the script became more common in the late 2000s. Unfortunately, options in Meitei Mayek fonts are still limited, meaning that the visual identity of book text is largely homogenous.

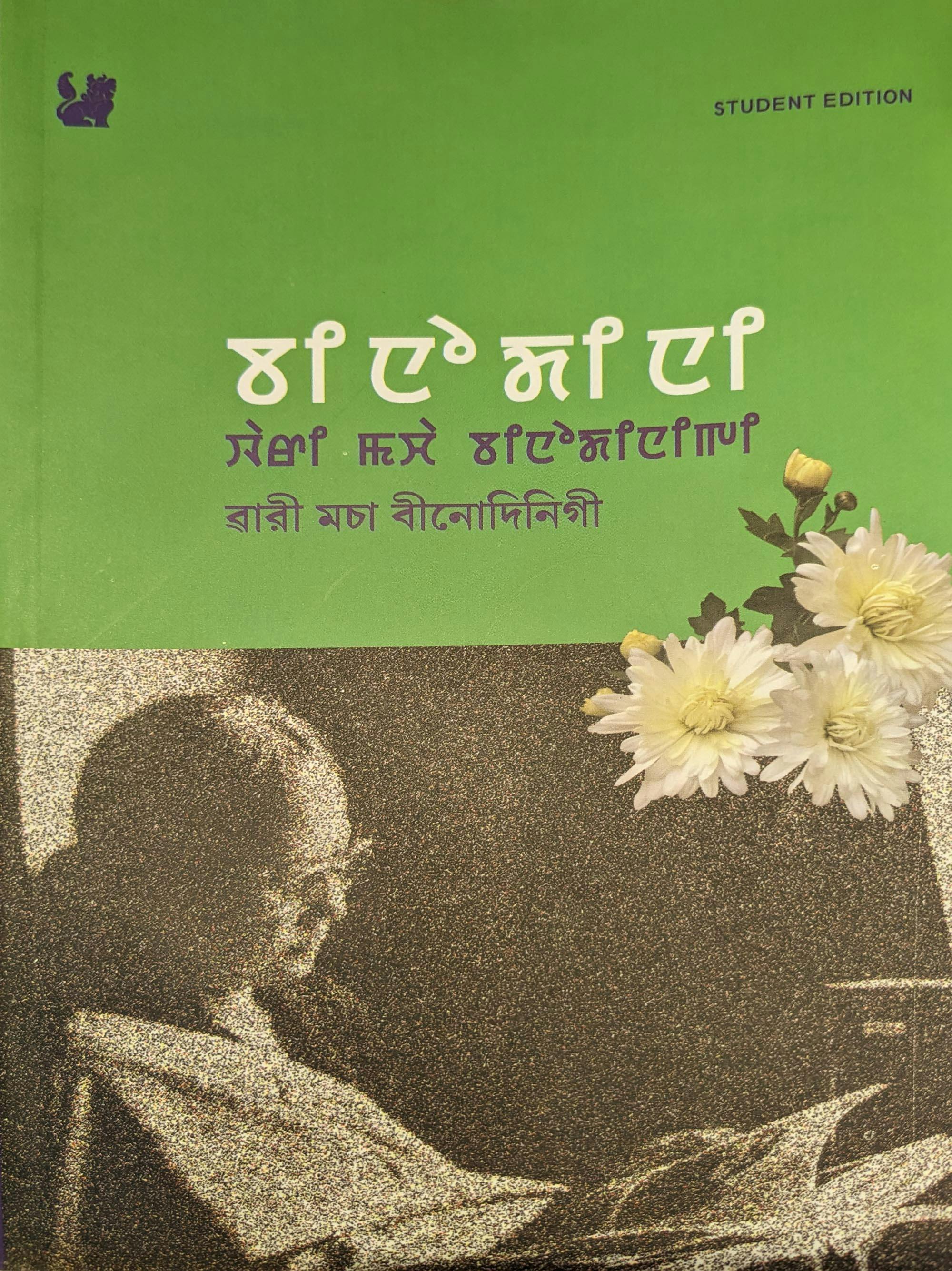

According to Ukiyo Bookstore, Imphal, the popularity of Meitei Mayek books is picking up, but they are primarily purchased by younger readers, with a younger generation of artists, writers and musicians using Meitei Mayek for their own work. The shop’s shelves also carried books printed entirely in Meitei Mayek, branded as ‘student editions’.

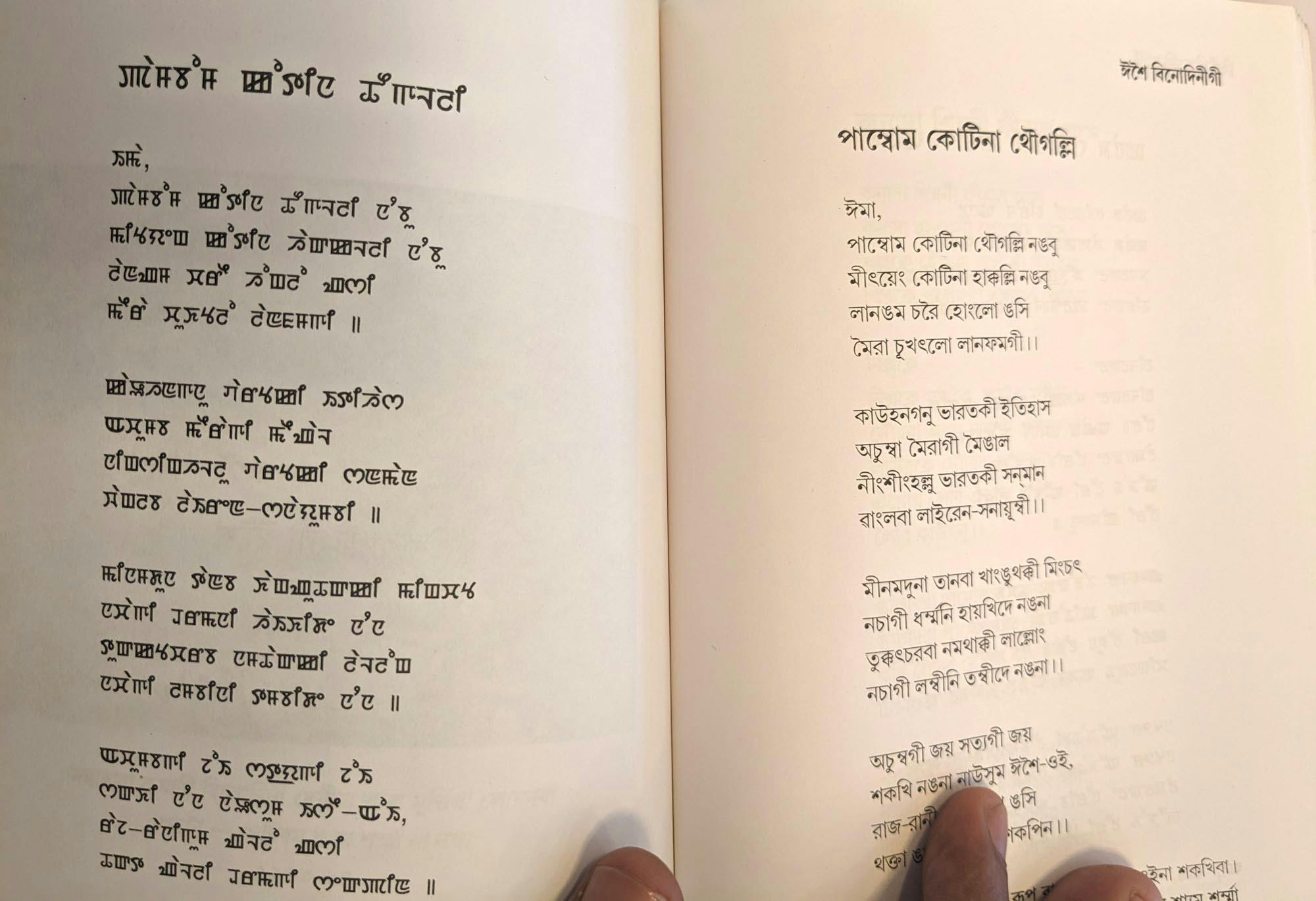

Another common pattern is books that use both scripts in their content. Some are actively biscriptal, with half the book in one script and the other half in the other. Some are printed in two editions in Meitei Mayek, one in Bengali script and one in Meitei Mayek. Another interesting trend is reprinting books originally published in the Bengali script, which some prominent Meitei writers have done, participating in script adoption while also bringing their work to a new generation.

At present, books solely in Meitei Mayek are still a minority, and they exclude the large segment of Meitei readers who are literate only in the Bengali script. Biscriptal books and editions, on the other hand, are growing in popularity as a practical compromise.

Journalism

The first periodical in Meitei was the magazine Meitei Chanu, printed in 1922 in the Bengali script, as was the norm in Meitei printing. Until the early years of the 21st century, Meitei-language journalism was entirely in the Bengali script, and so, just like with books, older Manipuris grew up reading newspapers in the script.

In the early 2000s, in parallel with a more forceful push for Meitei Mayek, some newspapers decided to include this script as well. The first to do so was Huiyen Lanpao, under its founding editor Salam Bharat Bhushan.

Over the years, other Meitei-language dailies followed suit, and MEELAL has also pushed journalists to adopt the script. However, these efforts have been constrained by the realities of Meitei Mayek literacy, since a complete switch to the script would essentially leave newspapers incomprehensible to most readers, who belong to older generations.

In 2021, MEELAL issued an order for newspapers to be printed entirely in Meitei Mayek from February 2022, subsequently extending the deadline to 15 January 2023. After discussions with journalists, the order was amended again, to a quarter of newspaper content from 15 February 2023.

When we visited Imphal in February 2023, most dailies were still being printed primarily in the Bengali script. Just as with books, we noticed numerous patterns of biscriptal accommodation and co-existence.

Mastheads for newspapers are in both scripts as well as Latin, with the Bengali script and Meitei Mayek versions usually given equal weight. Articles themselves are mostly in the Bengali script, although a few articles per page are written in Meitei Mayek.

Interestingly, government notices in newspapers carry the same message in both Meitei Mayek and the Bengali script. Cartoons utilise both as well, repeating the same message, and some readers told us they use these short parallel texts to learn Mayek.

Different newspapers vary in their usage of Meitei Mayek. Poknampham uses the script more sparingly than Sanaleibak, for example, whereas _Naharolgi Thoudang _is more generous in the real estate it offers Meitei Mayek. As of today, Huiyen Lanpao is the only major daily that also sells an edition completely in Meitei Mayek.

However, journalism in Manipur is already in a precarious situation, and newspapers run on very tight margins. The largest problem facing this industry is obviously the lack of a mass readership in Meitei Mayek.

A switch to this will put additional pressure on publications, since staff will have to be trained to read and typeset in the script, not to mention the challenge of procuring equipment. Meitei Mayek fonts are also limited, and working with existing fonts can be challenging because of rendering issues and minimal word processor support. All these factors put additional financial pressure on struggling budgets.

There is also a sizable community of Meitei speakers outside Manipur itself, who are not learning Meitei Mayek and continue to use the Bengali script.

Teaching

Thoungamba Khangembam, a local educationist, spoke to us about the various issues teachers and those in education face in ensuring that children learn Meitei Mayek.

Local children, for example, find Meitei Mayek intuitive to learn and remember, which they do from kindergarten onward. However, there are few resources to assist teachers themselves in learning the script. Meitei teachers are trained by the local government to teach Meitei Mayek, and are assisted by MEELAL activists. Older teachers in particular have trouble switching from the Bengali script, since they have many years of experience teaching children in it.

In Manipur’s hillside districts, where Meitei is not the local language, there are fewer teachers of Meitei in general, but most are trained in Meitei Mayek.

Another issue Thoungamba drew attention to was the gap in knowledge between children and their parents. Parents are not usually familiar with Meitei Mayek, which makes it difficult for them to assist with their children’s homework or learning. At the same time, older books and reading materials are primarily in the Bengali script, and are inaccessible to the younger generation educated solely in Meitei Mayek.

Thoungamba also highlighted adult education, as a means to bridge the script divide. Online resources and training have been helping older Meitei speakers gain familiarity with Meitei Mayek, through practice. Interestingly, although adult learners accept the difficulty inherent in learning a new script for their own language, they still see it as important to learn (even if they don’t or cannot).

Response to promotion

Meitei Mayek is universally seen as more representative of Meitei identity than the Bengali script is, even among the large section of Manipuris who cannot read it. There is very little objection to the promotion of the script from Meitei speakers, although some of the measures taken are seen as hasty or too uncompromising. It is also a source of pride that the language has its own unique script, and indeed one with a history of many centuries. The narratives presented by various Meitei culture-focused groups on the script and its place in Meitei literary culture are widely accepted.

In interviews conducted in Imphal, respondents who could not read Meitei Mayek were happy that the script was being actively promoted, but expressed some dissatisfaction about feeling excluded due to being unable to read their own language. Many also stated that they wanted Bengali-script support to be continued, particularly to accommodate older generations. After all, most Meitei speakers over 25 are primarily proficient in the Bengali script.

One complaint was that the somewhat sudden replacement of the Bengali script in the public sphere had created a gulf between audiences literate in one or the other script, removing a large section of the population from engaging with Meitei in the public sphere.

Another issue was the potential loss of the ability on the part of younger audiences to read older written material, leaving them more distant from their own history. Most printed samples in the language at the Manipur State Archives and any of Imphal’s older bookstores are in the Bengali script. Interestingly, most staff members at local cultural groups and government bodies working with Meitei literature and culture could not read Meitei Mayek at all.

However, even in these circumstances, the introduction of Meitei Mayek itself is not being called into question – only the lack of sufficient accommodation of it.

More complicated is the response of non-Meitei Manipuris to Meitei Mayek, especially in the face of efforts to preserve their own ethnic identities. For example, textbooks in Meitei Mayek were set on fire in Manipur’s Churachandpur district, and vehicles with Meitei Mayek licence plates or writing on them were also vandalised in Senapati district; in neither area is Meitei the dominant language.

These actions were reactions to statements by MEELAL on the promotion of Meitei Mayek in these regions, rather than an objection to the script or the language itself. The opposition faded with time, and now children from these communities are learning Meitei Mayek. In Imphal, members of these communities reacted positively to the revival of Meitei Mayek, with many asserting that Meitei should be written in its ‘own script’ as well.

Unicode

Sociologist Dhiren Sadokpam shared with us that he had been involved in developing the first Unicode font for Manipuri, back in the early 2000s. Instead of support, he and his collaborators were met with opposition, since it was believed that a Unicode font would make Meitei speakers dependent on foreign companies for the digital usage of their own font.

As Meitei Mayek increased its digital presence, a few other fonts were developed, and Unicode fonts also caught on. Currently, the Meitei Mayek font by E-Pao, an online publication, is the most widely used for text input. However, certain rendering issues have been reported, and in addition, word processors, including those that are part of the Google Workspace, largely do not support Meitei Mayek text, making it harder to produce and edit text in the script. These issues compound further the difficulties in promoting Meitei Mayek.

Ol Chiki

Ol Chiki is the preferred script of speakers of the Santali language. Santali is a Munda language (a branch of the Austroasiatic language family) spoken in eastern central India by around 7.6 million people. However, unlike Meitei and most of India’s other Scheduled languages, Santali lacks primary official status in a linguistic state of its own, since its speakers are spread out across a large geographic area and do not form a majority in any Indian district.

The geographical distribution of Santali across other linguistic zones dominated by other standardised languages – Hindi, Bengali, Odia, Assamese – has resulted in the language being written in different local scripts in each region – Devanagari, Eastern Nagari (or Bengali-Assamese), Odia – plus the Roman alphabet.

This splintering of Santali has made the pursuit of graphical unity under Ol Chiki an enticing project. At the same time, the lack of a Santali linguistic state (or administrative region) has meant that government support for Ol Chiki took time to develop, and most promotion initiatives historically came from civil society and activists.

Origins

Uniquely for one of India’s major scripts, Ol Chiki was the brainchild of a single individual, the Santali thinker and writer Raghunath Murmu (often given the epithet Pandit, ‘learned man’). Murmu devised the script in 1925, as a student.

Ol Chiki was created as a ‘rational’ script, and closely represents the sound system of Santali, with no conjuncts or combining forms. It includes letters for phonemic features found in Santali but not in surrounding languages, in particular <ᱽ>, used to mark non-ejective stops at the end of words.

As a wholly modern script, there are no pre-print manuscripts or inscriptions in Ol Chiki. The earliest examples of writing in the language come from Raghunath Murmu’s own notes, and woodblock printed reproductions of these letters. Ol Chiki was first demonstrated to the public in 1939, although Hor Sereng was the first book to be printed in Ol Chiki in 1936.

Spread

Pandit Murmu began teaching Ol Chiki to his fellow Santals across various districts, and even prepared a set of primers to teach the script. He set up Chandan Press in 1946 (later renamed Ol Press) to print books and periodicals in Ol Chiki, and founded the ASECA (Adivasi Socio-Educational and Cultural Association) in 1964 to promote adivasi cultural heritage, including Ol Chiki. It was also around this time that the first metal font for the script was cast, in Calcutta.

In the following decades, ASECA activists and some Santali intellectuals continued to use Ol Chiki in local publications and teaching materials, although most Santali speakers used local scripts instead, especially in West Bengal and Jharkhand, the latter using mostly Latin. The ASECA organised regular training camps for the script, following in the footsteps of its founder, ensuring that the script remained in popular consciousness.

As sociolinguist Nishaant Choksi writes, ‘During the late 1950s and early 1960s, [Raghunath] Murmu started touring the Santali-speaking area and offered the Ol Chiki script as a way of unifying Santals across graphic boundaries.’

Language and education policy

For many decades, Ol Chiki was sustained solely by the activists and writers in the Santali community, who continued to teach the script and use it in their journals and writings. No government support was forthcoming, since the language lacked a political bloc of its own.

In 1979, Jyoti Basu, the Chief Minister of West Bengal, recognised Ol Chiki as the script used for Santali. While this signalled external recognition, it did not immediately translate into official policy.

This changed in the early 2000s, when Santali was added to the 8th Schedule, after decades of campaigning and calls from activists. Importantly, Ol Chiki was recognised as the Santali script.

Including one of the most visible and widespread adivasi languages in the 8th Schedule, for the first time in India’s history, was also a symbolic move, intended as an outreach to India’s adivasis. Santals are an important vote bloc in their districts, and this act of recognition reflected their growing political importance.

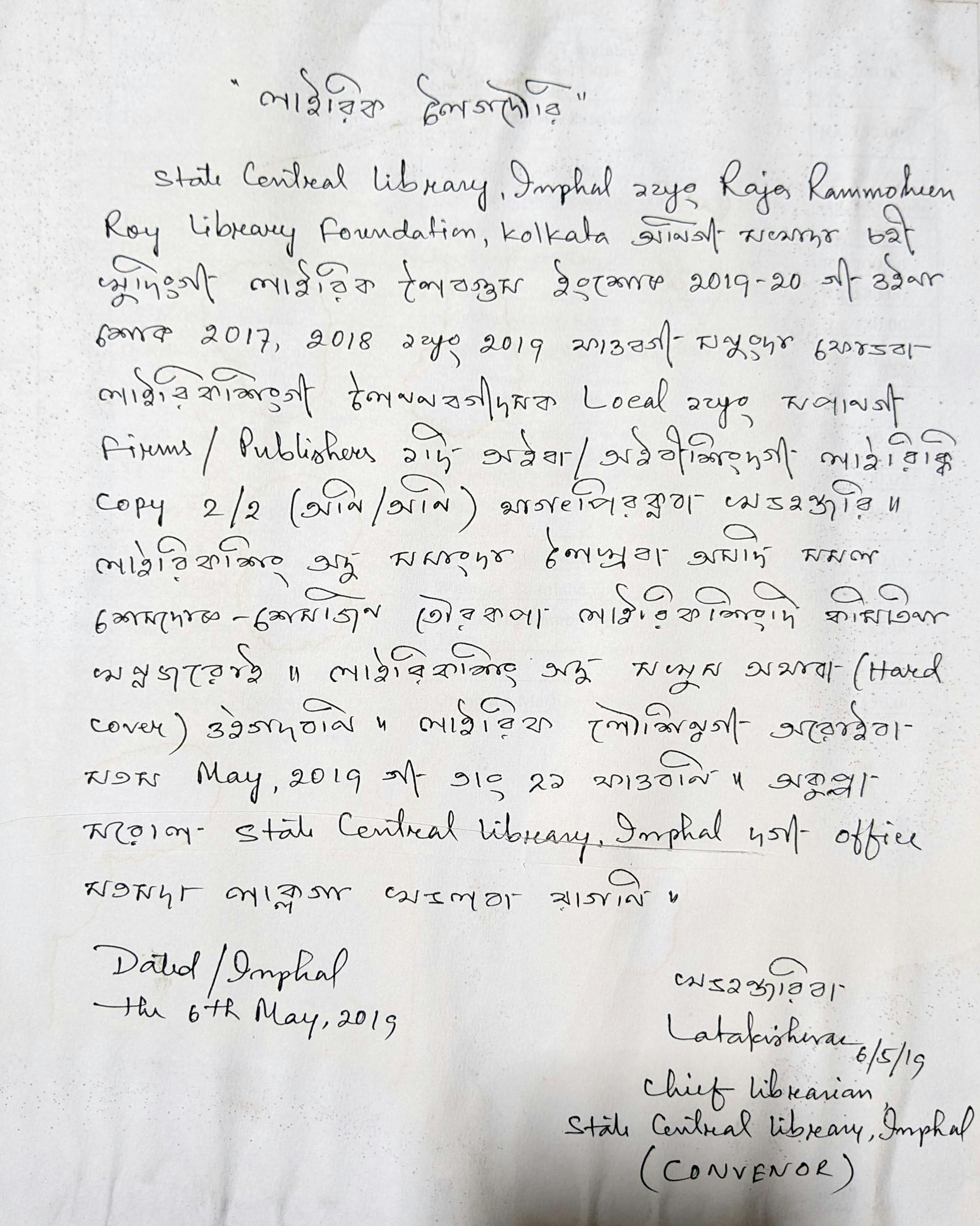

After its inclusion in the 8th Schedule, government bodies across India had little choice but to support Santali and Ol Chiki. The Central Institute of Indian Languages (CIIL) has printed materials in Ol Chiki, while the Sahitya Akademi (Literature Academy) began to promote Santali literature and offer awards to writers.

Today, UPSC (Union Public Service Commission, the Indian civil service) exams, sat by millions of Indians every year, can be taken in Santali (with questions in Devanagari), answered in Ol Chiki. State civil government exams in West Bengal can be taken in Santali, with papers entirely in Ol Chiki.

The governments of West Bengal and Jharkhand both recognise Santali as an additional working language. Government offices across both states increasingly feature Ol Chiki signage, reflecting local government policy. Odisha is yet to include Santali as an additional language.

Public presence

In his book Graphic Politics in Eastern India, Choksi documents the various public manifestations of Santali community identity through Ol Chiki writing. He notes that the script features prominently in spaces where Santal speakers live and congregate as a community, marking their physical and cultural presence.

As a response to this, non-Santals have also begun engaging with the script in an effort to include Santali speakers and their presence in society.

Local government offices, hospitals, and even NGOs display Ol Chiki signage and circulate leaflets in Santali. Meanwhile, local politicians have adopted it for their manifestos, reflecting the growing importance of Santali speakers in politics.

With government support adding to community efforts, the script has entered the mainstream, and its presence in the public sphere has been firmly established by its speakers and government agencies.

Publishing

We spoke to Ashwani Murmu, a Santali activist involved in promoting the language and Ol Chiki, about the state of Santali publishing in Ol Chiki.

Identifying five main publishing houses across three states, Murmu contended that most publishing in Santali is not commercially viable, and is primarily done to preserve the language and disseminate knowledge and information. A smaller set of writers target literary awards, he adds. There are fewer printing presses, fonts, typesetters, and proofreaders, and a smaller market for distribution available to publishers. The publishing houses that have survived have done so by selling books in other languages, as well as stationery.

In addition, most Santali speakers who cannot access English books tend to be economically weaker, limiting their purchasing capacity – yet it is these speakers that need Santali books the most. Santali speakers as a whole have lower literacy levels, meaning that writers and readers utilising Ol Chiki form a minority in the community, albeit one that is growing decisively.

Journalism

Most Santali speakers read local newspapers in the dominant languages of their region, according to Ashwani Murmu. He pointed out how the dispersal of Ol Chiki presses meant that daily news would only reach Santali speakers from a distant source days after the event happened, rendering the information useless.

As such, there are no Santali language dailies. The most prominent periodical in Ol Chiki is arguably Fagun, a widely read monthly carrying local news not present in dailies. A few others exist as well, including the fortnightly Lahanti Patrika, which publishes in Ol Chiki and the Bengali script.

Hence, journalistic efforts in Santali lack commercial viability, much like book publishing, and what there is tends to be self-funded.

Teaching

Once only taught independently by local activists, the Santali language has now entered local education boards. West Bengal, Jharkhand and Odisha all offer Santali (in Ol Chiki) as a subject in local schools and colleges, although not consistently across classes in some cases. Santali is also a subject at higher education institutions, and is even offered as a medium of education in some institutions.

In all three states, textbooks are printed in Ol Chiki, and Assam is similarly considering introducing this.

The first college-level course in Santali was taught by a CIIL trainee, and their students went on to become professors elsewhere, further spreading Santali education at the tertiary level.

Response to promotion

Ol Chiki is widely associated with the assertion of a distinct Santal identity, and as such, is viewed very positively within the community. Cultural agitations and protests around Santali rights prominently feature slogans and posters in Ol Chiki.

Any promotion of the Santali language inevitably involves promotion of Ol Chiki as well. Local politicians have taken up the cause at multiple points, including the chief minister of Jharkhand, Hemant Soren (himself a Santal).

However, Ol Chiki has had less success in the Santali-speaking parts of northern Jharkhand (commonly termed the Santal Parganas), where the Latin script was introduced for writing the language by European missionaries. These speakers often prefer Devanagari over Ol Chiki.

Unicode

Fortunately, Ol Chiki is a simple script, and it is easy to render on digital devices. Since the release of Android 5.0 in 2014, mobile devices have supported Ol Chiki, prior to which support was limited. C-DAC (Centre for Development of Advanced Computing, a government of India body) worked on a Unicode font for Ol Chiki, which was distributed for free. Ram Chandra Murmu, a Santali speaker, contributed to the development of the font.

New graphic identities

Both Santali and Meitei have succeeded in bringing their scripts to the forefront of their respective linguistic environments, and to a position of prominence, creating a model for other language communities, and for studies on scripts elsewhere across India and the world.

Ol Chiki has gone from a simple script devised by a community leader, passed down by activists and enthusiasts, to a potent graphical marker of Santali identity that non-Santals have come to acknowledge and respect, even receiving national recognition. Through Ol Chiki, Santali speakers have carved out a graphic space for their language amid the dominant languages of their surroundings, a conscious political and cultural assertion.

Meitei Mayek, on the other hand, is an example of a historical script revived through a language community’s desire to write its own history on its own terms. The distinctiveness of Meitei Mayek has come to represent Manipur’s unique historical trajectory, serving as a cultural rallying point in the face of political marginalisation.

In both cases, digital devices and language policy have proven instrumental in ensuring that these scripts remain in circulation, becoming inseparable elements of their language communities.

Despite how far they’ve come, both scripts have a long way to go in reaching parity with major Indian scripts in terms of the degree of visual and graphic diversity available to them. Font options and stylistic variation are still limited, but we are seeing this change with time.

Check our Typotheque Meetei Mayek and Ol Chiki fonts developed in collaboration with the local communities, or watch a short documentary about the process of creating the fonts. November Meetei Mayek and Ol Chiki are part of the larger November South Asia font collection.