Georgian alphabet, writing and typography

The origins of the Georgian writing script

Georgian writing script has a centuries-old history and is considered an important part of ancient Georgian culture. Research into the Georgian alphabet is ongoing, and opinions as to its origins vary widely, because it does not belong to any other series of alphabets. Since the 19th century, Georgian researchers, and those based elsewhere, have been trying to identify the period in which the Georgian script came into being. Some believe it originated in Western Georgia during the Hellenistic period, while others think it appeared even earlier. Leonti Mroveli, a prominent figure of the 11th century, connects the creation of the Georgian script to the Georgian king Parnavaz (3rd century BCE):

‘და ესე ფარნავაზ იყო პირველი მეფე ქართლსა შინა ქართლოსისა ნათესავთაგანი. ამან განავრცო ენა ქართული, და არღარა იზრახებოდა სხვა ენა ქართლსა შინა თვინიერ ქართულისა და ამან შექმნა მწიგნობრობა ქართული.’

‘And here Parnavaz was the first king of Kartli from the race of Kartlos. He spread the Georgian language, and there was no other language but Georgian in the land of Kartli. And he created the Georgian script.’ (Source: Georgian Chronicles, 9th to 14th centuries)

Renowned Georgian historian and linguist Ivane Javakhishvili believed that the Georgian alphabet had to have been created in the 8th century BCE, and the literary expert Ramaz Pataridze shared the premise upon which Ivane Javakhishvili based his argument. Backing his theories up via mathematical and astronomical studies, Pataridze suggested that the Georgian alphabet had been created by the elders (priests) from ancient Kolkheti-Iberia. According to his work, the names of the letters in the Asomtavruli alphabet, the principles of grouping, their ordinal and numerical values, graphic outline and mathematical-geometrical nature indicate the representation of the pantheon of pagan gods in the alphabet, the ancient calendars of the sun and moon, a synthesis of the findings of the ancient civilisations of Mesopotamia and Egypt, and the history of the creation of the most accurate calendar system by Georgians.

Three kinds of Georgian script

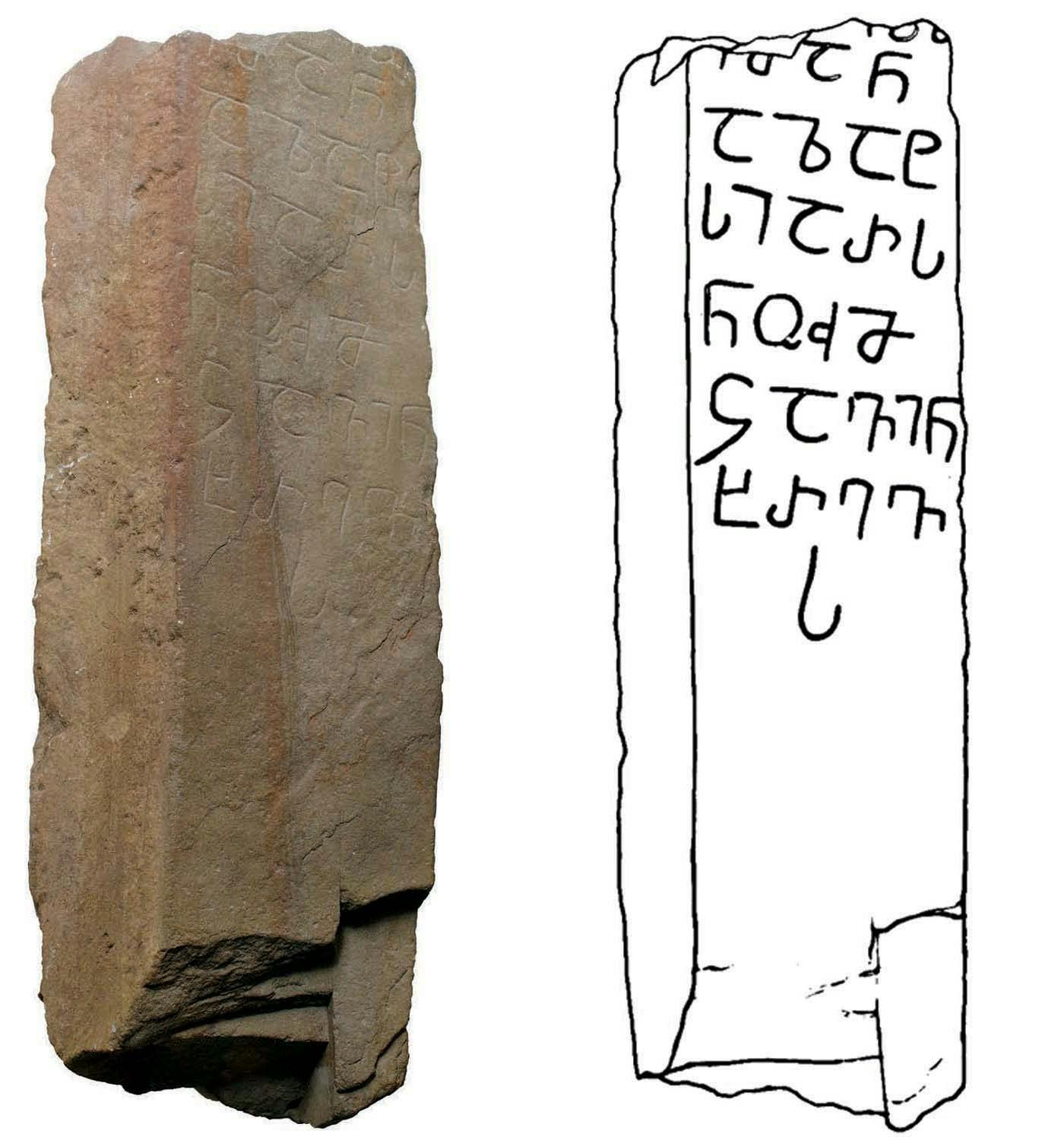

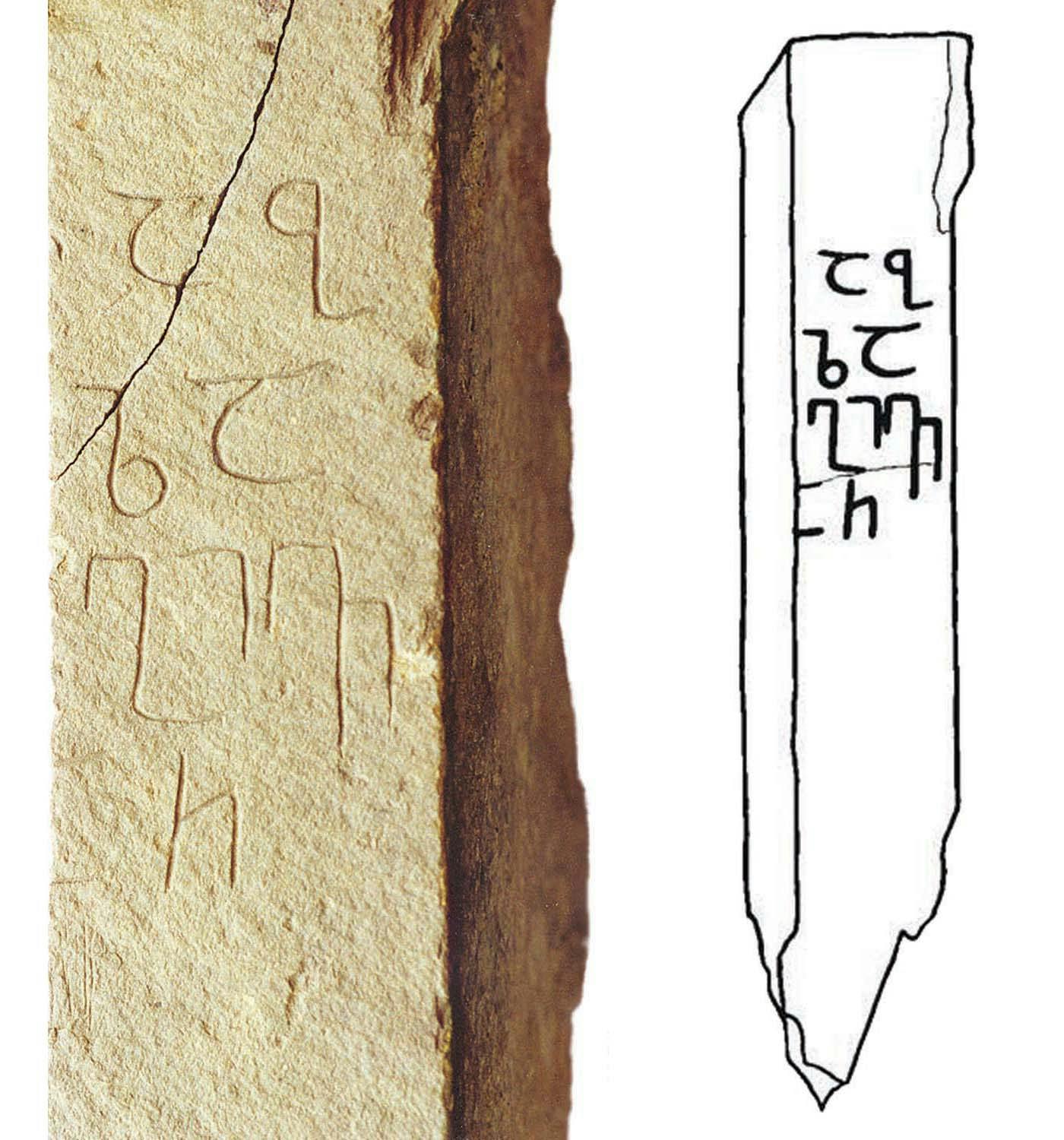

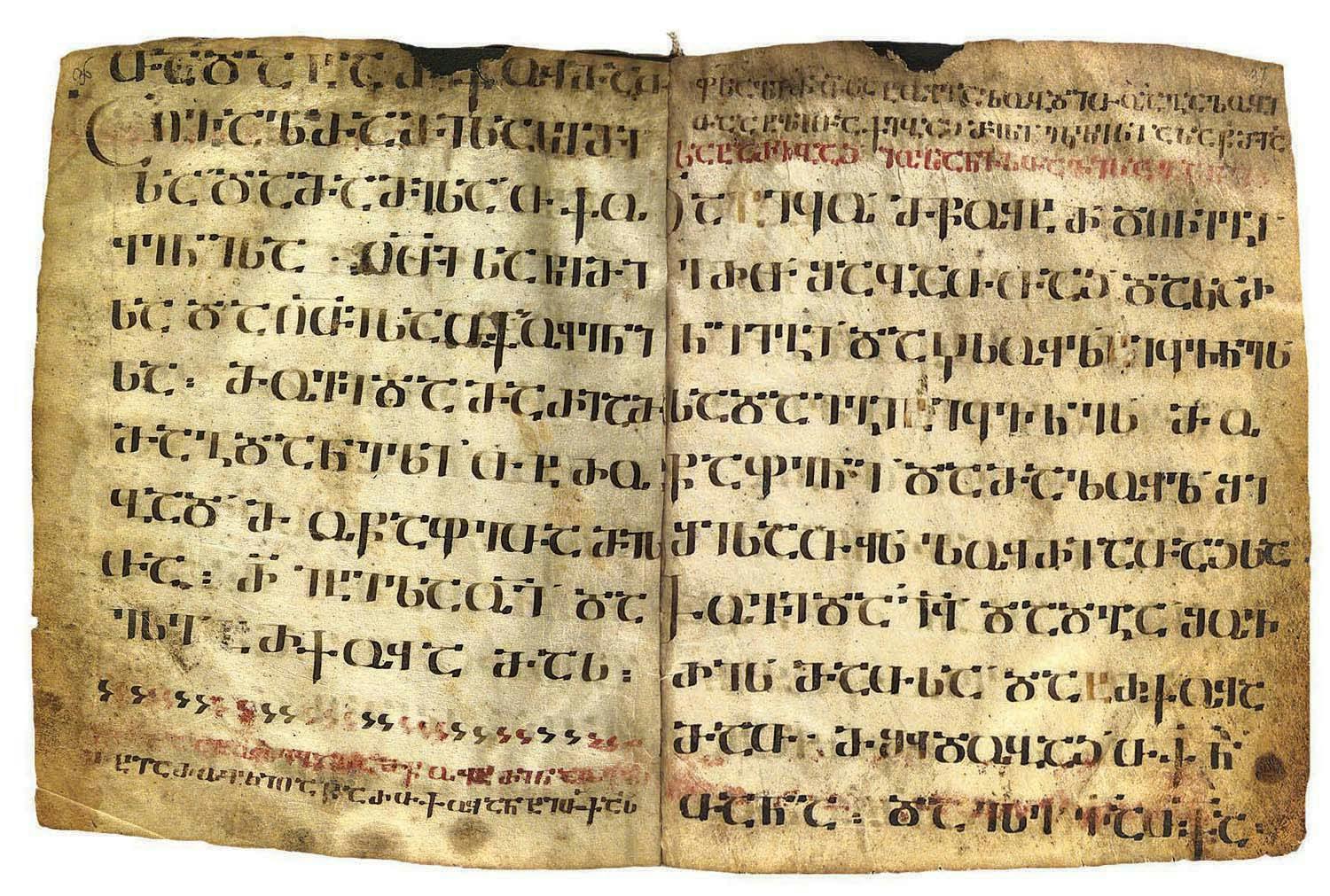

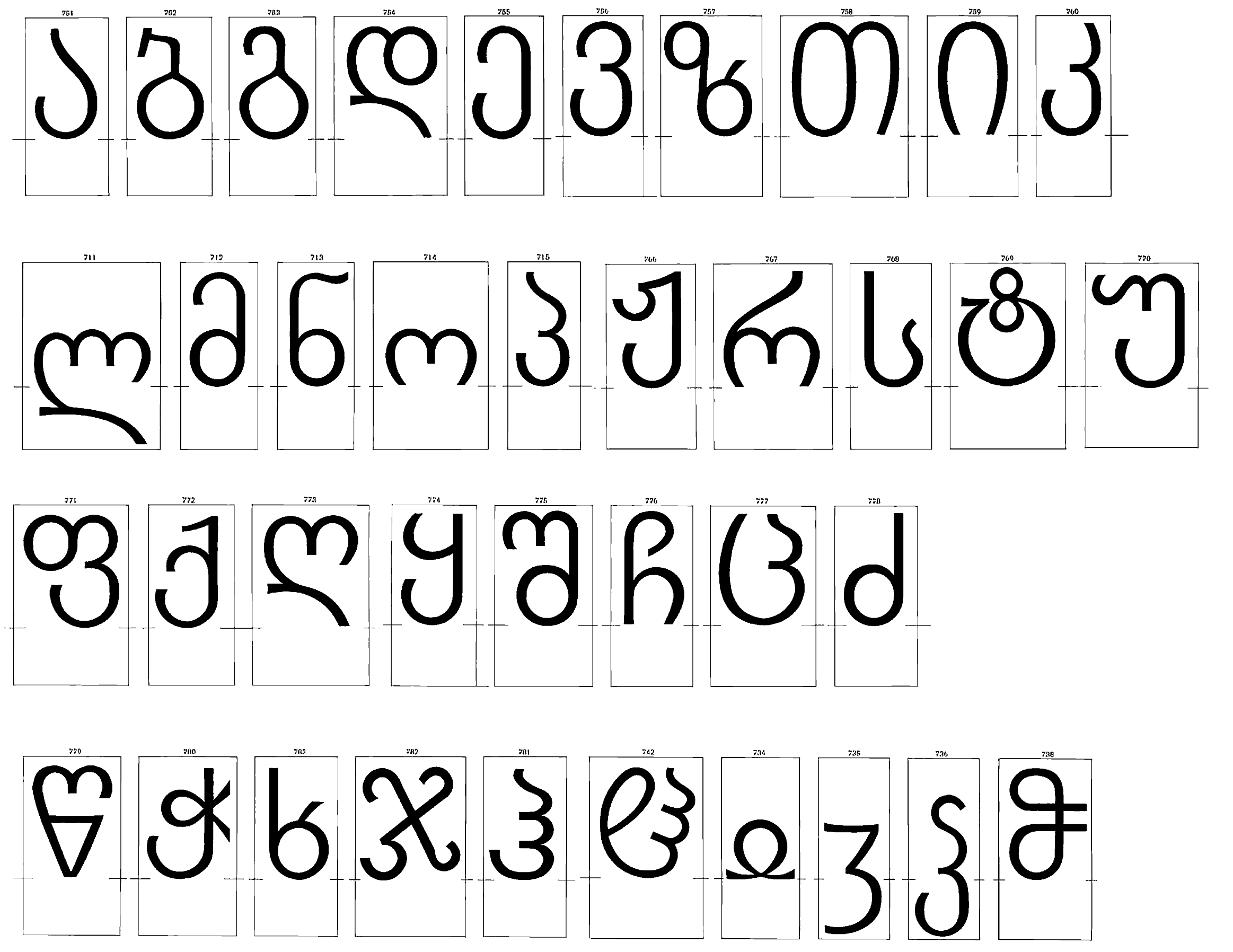

There are three kinds of Georgian script: Asomtavruli, Nuskha-Khutsuri and Mkhedruli (modern script). Chronologically, Asomtavruli, also known as Mrgvlovani (rounded), is considered to be the first; it is one of the unique writing systems among the few ancient scripts recognised in the world. The geometry of the Asomtavruli (Mrgvlovani) alphabet is simple and plain, being based on a circle, semicircle and straight line. Nine varieties of circle and straight line are used in its construction, and each letter has strict proportions and completely or partially fills the imaginary square. The oldest surviving scripts (5th century CE) are written in Mrgvlovani. Of these, the manuscripts found at Bolnisi Sioni Cathedral and Palestine are distinguished by graphic outlines of such sophistication that they must have undergone a long previous stage of development. This opinion is supported by the discovery of seven gravestones and their inscriptions during archaeological excavations at Nekresi. These stones had been used as secondary construction materials in the walls and wine-presses of a cellar built in the 4th century. A large number of academics (e. g. L. Chilashvili, Z. Aleksidze, R. Pataridze) assume that they date back to the pagan era, and in fact a pagan chapel with several tombs and an inventory dating from the 3rd to 2nd centuries BCE was also found beneath the cellar. It should be noted that none of the stones display any Christian symbols.

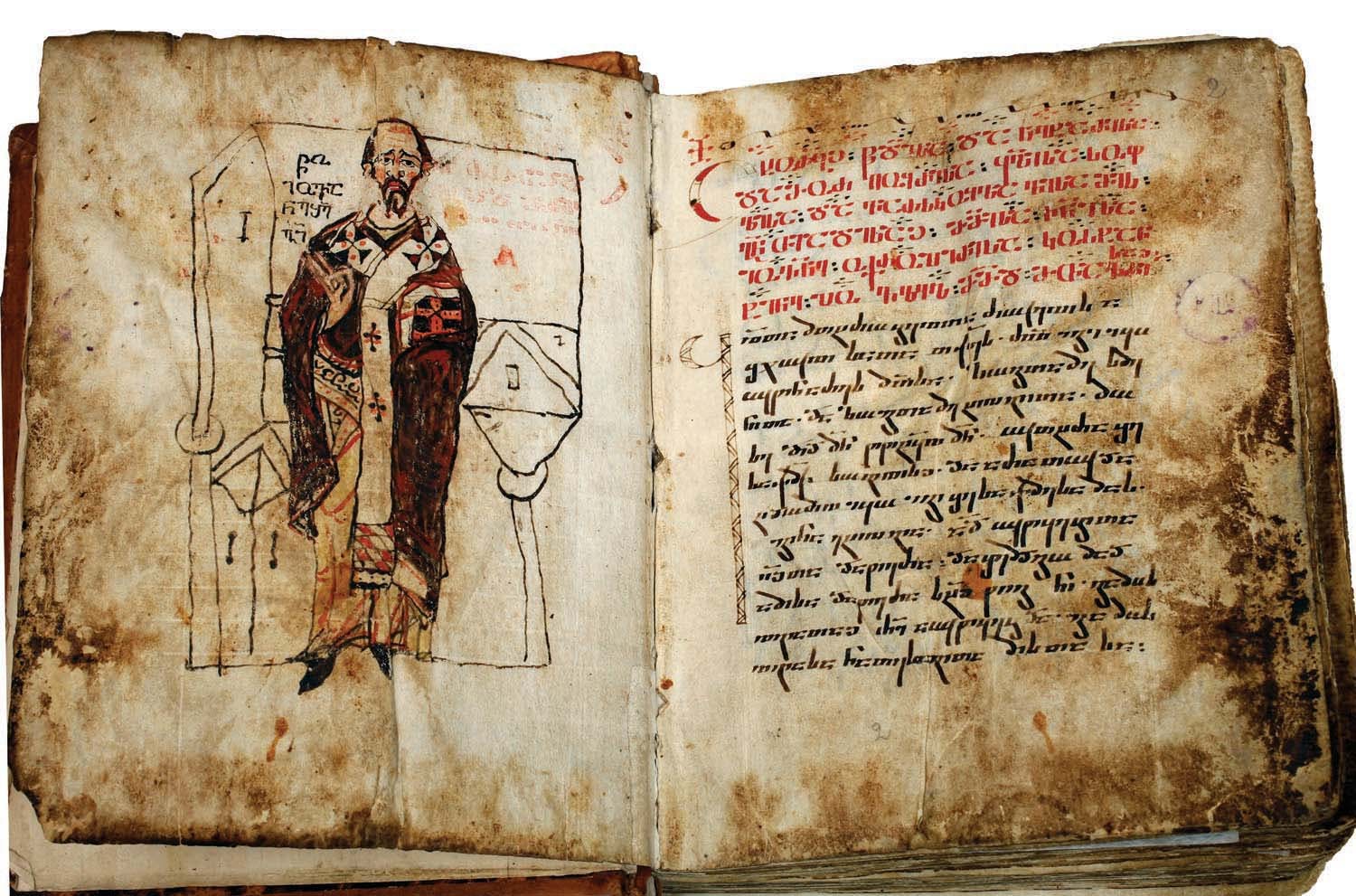

Examples of the Nuskha-Khutsuri script start to appear from the 9th century onwards, with the oldest inscription, from 835, found on the walls of the Ateni Sioni Church. A part of the Sinai ‘Mravaltavi’ (‘multi-text’) codex (manuscript of homilies, or explanations of the Gospels), from 864, is also written in Nuskha-Khutsuri. However, the majority of the inscriptions dating from the 10th to 18th centuries are still written in Asomtavruli. This script is used in manuscripts, but not exclusively — Nuskha-Khutsuri is also used. Sometimes the entire manuscript is written in Asomtavruli, with a codicil written in Nuskha-Khutsuri, or vice versa. Titles and initial letters are often written in Asomtavruli.

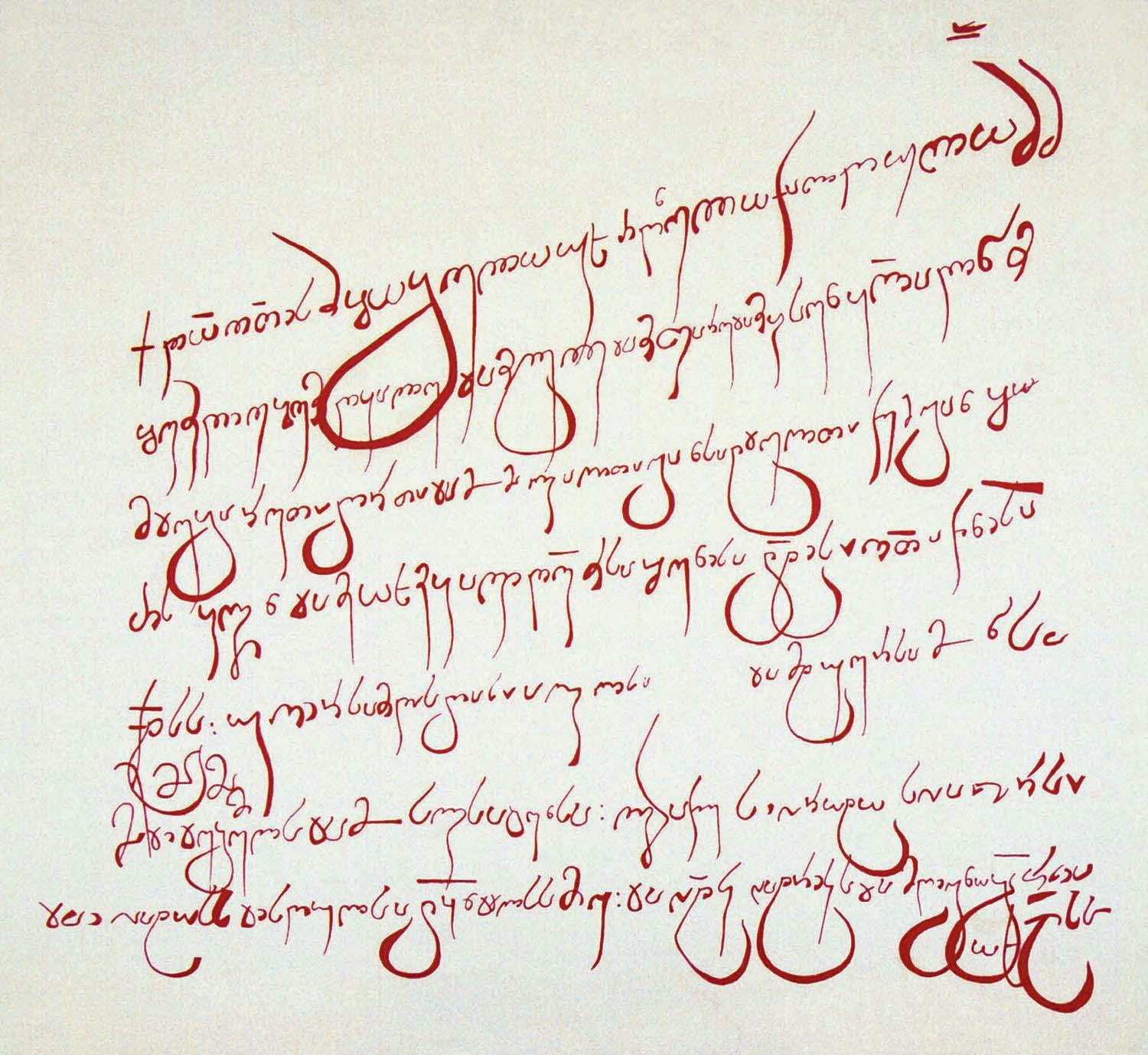

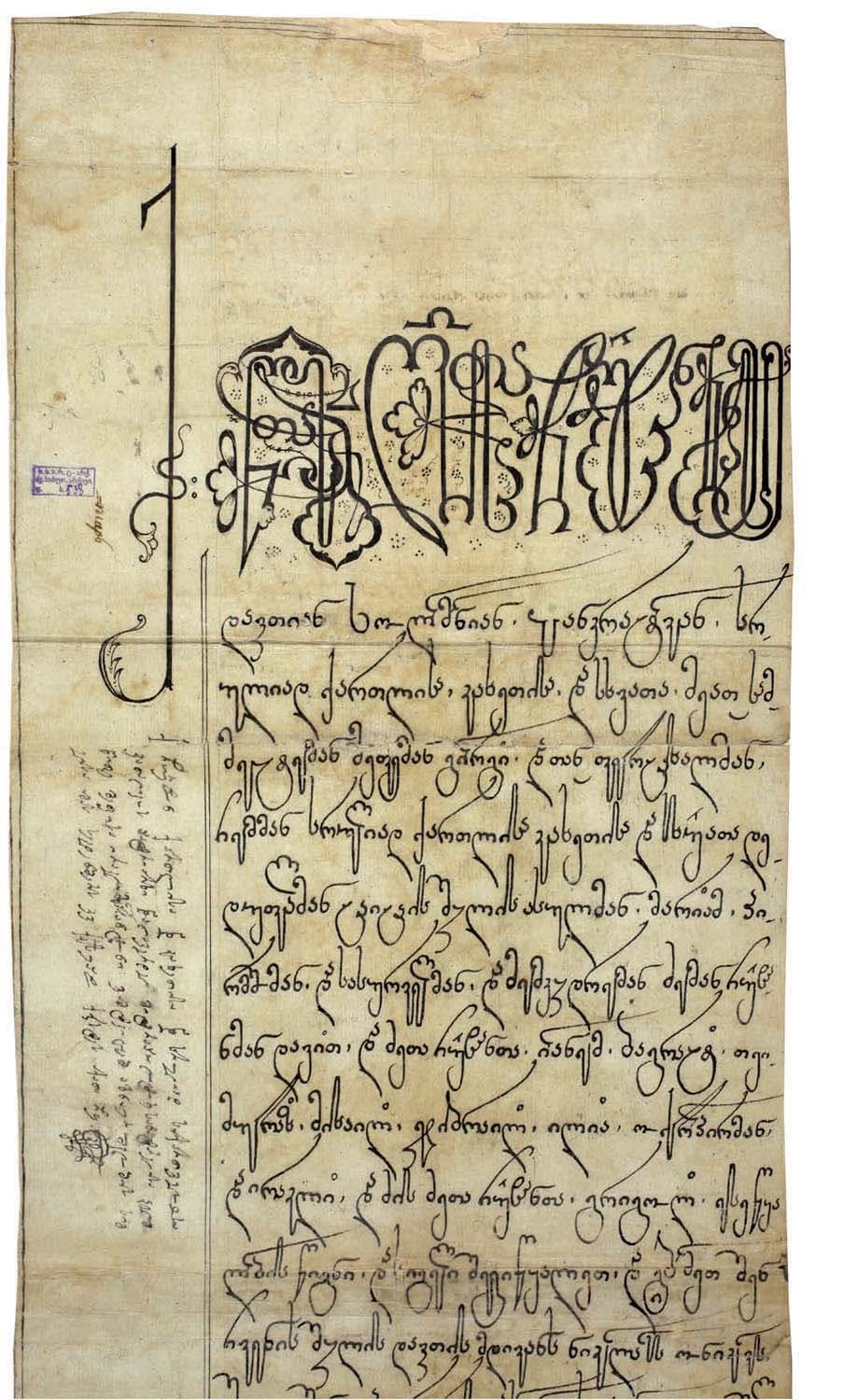

Mkhedruli, the third kind of Georgian writing, has been practised since the 10th century. The first Mkhedruli inscription was also found on the walls of the Ateni Sioni Church and dates back to 982–986. From then on, all three scripts coexisted, being used in parallel with each other for centuries. Among them, Asomtavruli and Nuskha-Khutsuri are found mainly on religious monuments, with Mkhedruli used more often in secular writing, although the opposite also occurs relatively frequently. It should be noted that in all three kinds of writing, each letter expresses only one phoneme, and has its own numerical value. In the modern Mkhedruli Georgian alphabet, there are 33 letters, this form being acquired in the 1860s and 1870s. Before that, there were 38 letterforms.

The influence of Christianity

Georgia is an ancient Christian country, and a follower of this faith since the first century, although the state recognition of Christianity came later, dating back to the beginning of the 4th century. During the 4th and 5th centuries, exquisite Christian basilicas and domed churches were built, and now there are several thousand churches across the country. As a result, the oldest examples of Georgian writing are preserved in the form of epigraphic monuments. These comprise stone-cut, mosaic, embossed and mural inscriptions, with the oldest among them being lapidary inscriptions on stone slabs used for church walls, stone crosses, tombstones and sarcophagi. The inscription either tells us about the construction of the temple or refers to the founder, religious or secular authority, donor or craftsman. The fact that the inscriptions are from many different times and contexts indicates that the church was a special place of knowledge during such times, a chronicle of the country.

In addition to epigraphic monuments, more than 10,000 Georgian manuscripts have survived. Those from the 5th to 9th centuries contain religious literature, and from the 10th to 12th centuries consist of philosophical, historical and secular writings. Most of them were created in Georgia, and some in Georgian monasteries abroad — in Palestine, Jerusalem, Mount Sinai, Athos and Bulgaria — which were also cultural and educational centres at the time. Many important books, including translations, were being written and transcribed, with famous figures living in the country at different times: Giorgi, Ioane and Eqvtime of Mtatsminda, Giorgi the Lesser, Ioane Zosime, Ioane Petritsi, Ephrem the Syrian and others.

Writing materials in Georgia

The most common writing material in ancient Georgia was parchment, which was made from sheep, calf, goat or deer skin. Parchment was inscribed with a pen cut from a reed stem, with a specially made black or red mixture, known as ‘Tsamali’ [drug]. The ink was called ‘Shavi’ (black). In 2001, during examination of the foundations of Svetitskhoveli in Mtskheta, writing equipment was discovered that dated back to the 2nd century BCE, comprising gold pencils and silver styluses. Until the 11th century, all manuscripts in Georgia had been made on parchment, with approximately a hundred sheep skins being needed to create an average-sized manuscript book. Parchment was a very expensive writing material, so old text was often scraped off, paint or ink removed, and a new text superimposed. A parchment that was treated in this way was called a palimpsest. The oldest Georgian manuscripts to have survived are preserved on palimpsests, some of them held in the Bodleian Library in Oxford, the University of Cambridge and the National Library in Vienna.

The oldest Georgian manuscript is the Sinai Mravaltavi (The Sinai Polycephalion), which was rewritten in 864 at the Holy Lavra of St Savas (Jerusalem). This was gifted to the Monastery of St Catherine, built in the 6th century, at Mount Sinai and is still kept there. Across the last three pages of the manuscript, in 981, Ioane Zosime wrote: ‘Qebai da Didebai Qartulisa Enisai’ (Praise and Glory of the Georgian Language), and it is in this work that he also talks about King Parnavaz and the spread of Georgian writing in the 3rd century BCE.

From the 14th/15th centuries, paper began to be imported from Venice in Italy and from Damascus. In the 15th century, printing presses began to be developed and the first books were printed, completely changing the way the Georgian alphabet was used over the centuries. New challenges included the creation of typefaces. During the 17th and 18th centuries, quill pens were also introduced.

The beginnings of print

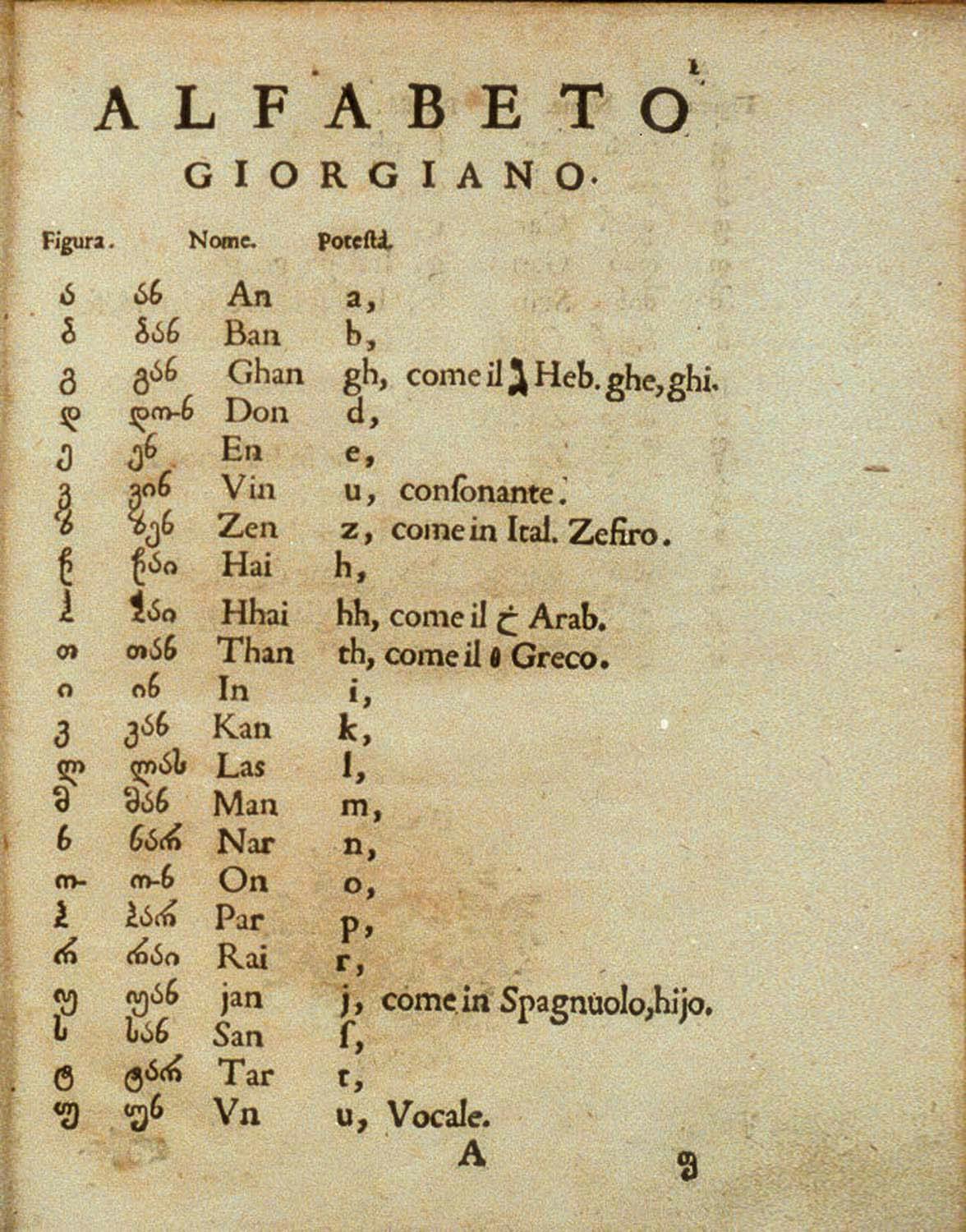

The first Georgian book, a Georgian–Italian dictionary, whose authors were the Italian printer Stefano Paolini and the Georgian diplomat and scribe Niceforo Irbach (Nikoloz or Nikifore Irubaqidze-Cholokashvili, c. 1585–1659), was published in Rome by the Propaganda Fide in 1629. A font needed to be cast, in order to quickly create and distribute printed products.

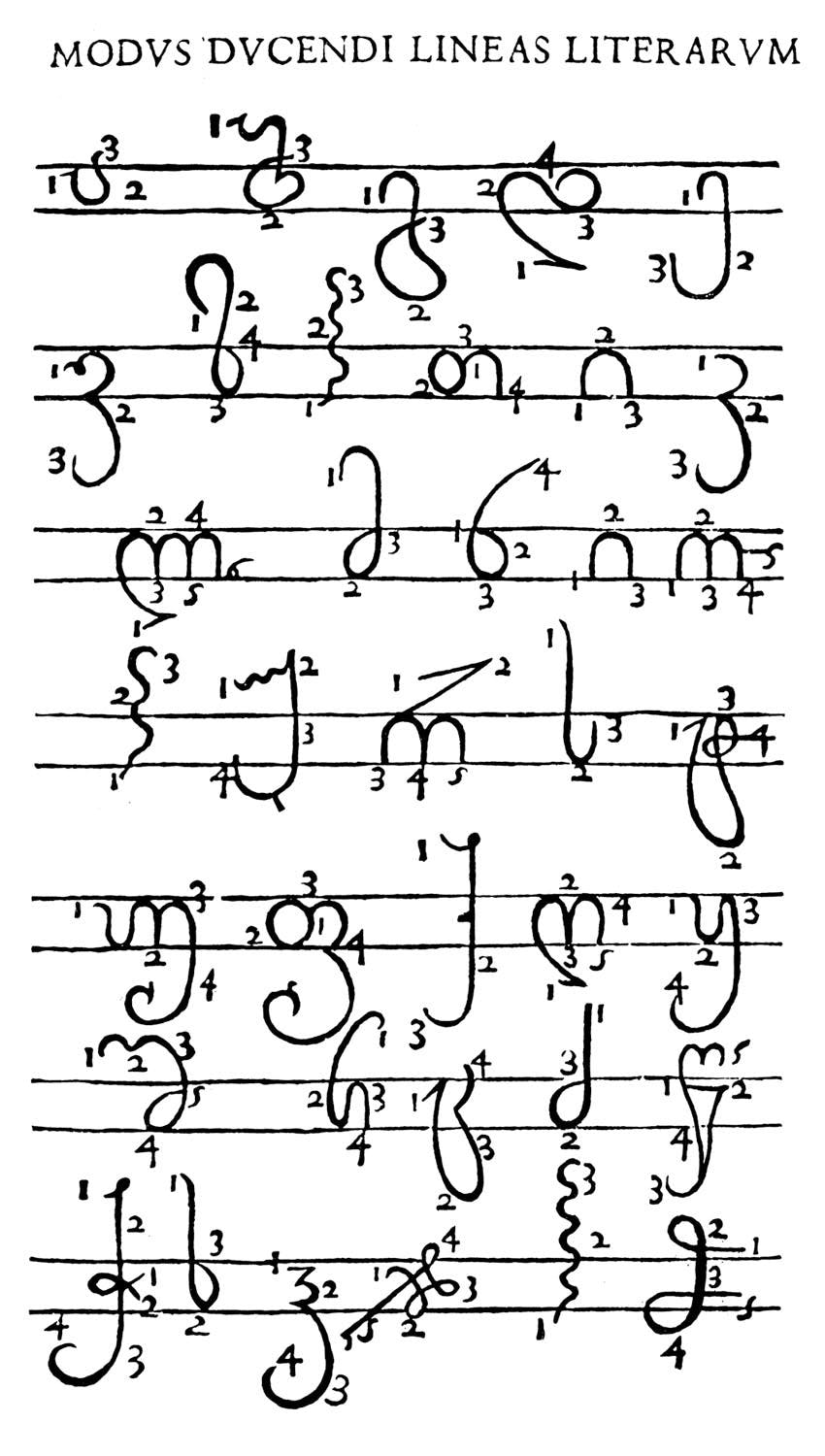

During this period, Latin typefaces were no longer created based on manuscripts, but since the outlines of Georgian letters and signs were foreign to Italians, the font was cast according to the letters found in handwritten correspondence of the King of Kartli, Teimuraz I (1589–1663), which was brought to Italy for Pope Urban VIII (1568–1644), by the king’s ambassador, Niceforo Irbach. Therefore, the first Georgian type is distinguished by the excess of bindings, and by the non-linearity and non-uniformity characteristics of manuscripts; each letter is cast both separately and linked to another letter.

The next Georgian typeface was made in Moscow in 1705 by the order of King Archil II (1647–1713), and ‘Davitni’ (The Book of Psalms) was printed in the same year. This was followed by the Stockholm typeface of Prince Alexander of Imereti (1674–1711) and the typeface commis-sioned by Alexander’s father Prince Archil, im-plemented by the Hungarian printer Miklós Kis.

In 1708, this typeface emerged in Georgia as well, following the establishment of a printing house in Tbilisi by King Vakhtang VI (1675–1737). At the king’s request, the famous Romanian clergyman of Georgian origin, scribe, educator and preacher, Metropolitan Antimoz Iverieli (1650 or 1660–1716) sent Hungarian–Wallachian master Mikhail (Mikhai Ishtvanovich) to Tbilisi to take control of the publishing business. It was he who created the typeface, with which all the famous editions that came from the Vakhtang printing house were printed.

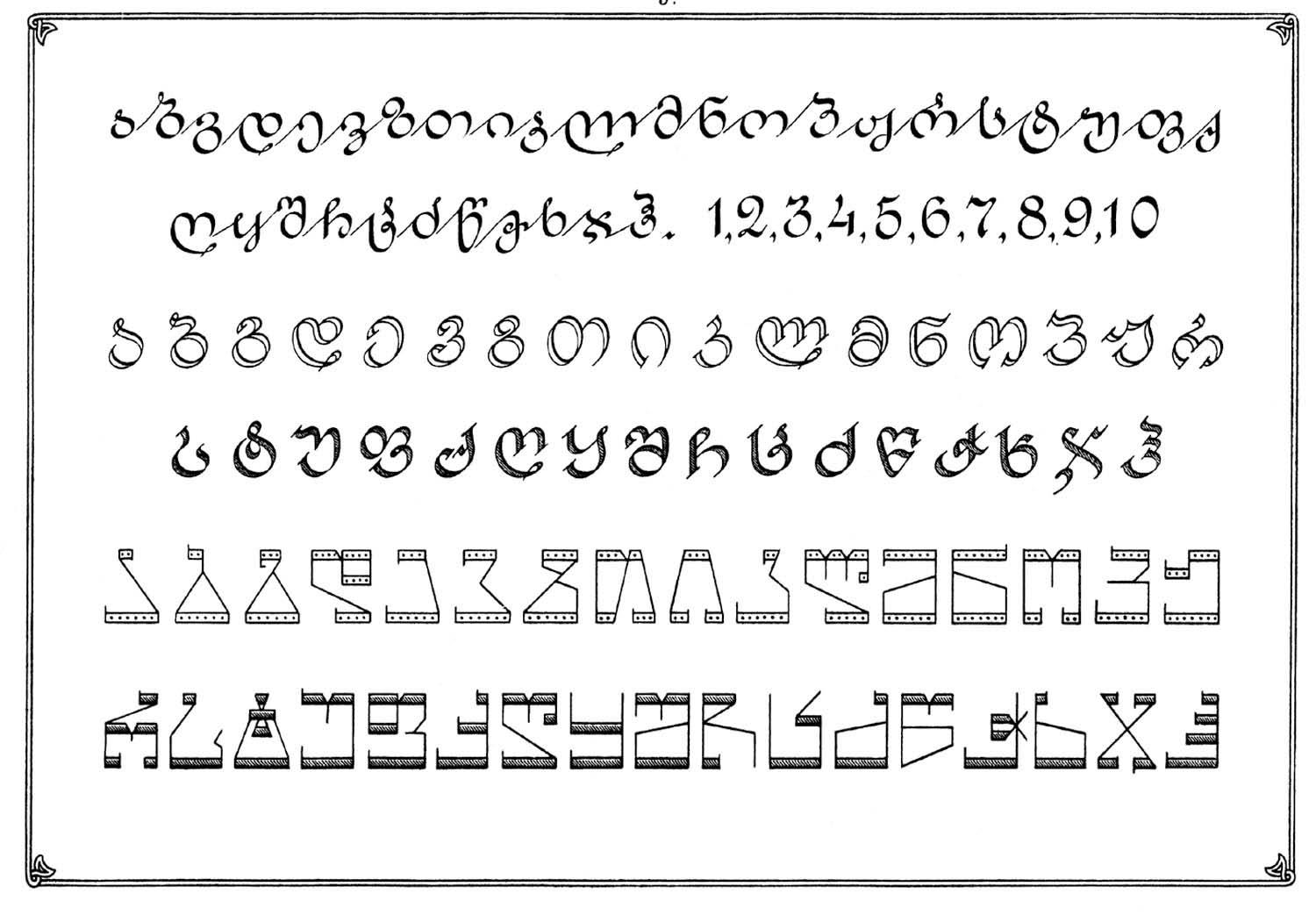

In the same period, the first versions of Georgian Asomtavruli and Khutsuri types were cast, although the main line of development of Georgian typefaces is revealed only in relation to Mkhedruli types. A total of 20 books were printed at Vakhtang VI’s printing house, and if we include repeated editions, the number rises to 23. The first was the Bible (1709), in which only one-size Mkhedruli and Asomtavruli types are used. From 1710, the situation changed — fonts of different sizes started to appear, and the printing process was improved.

The development of type

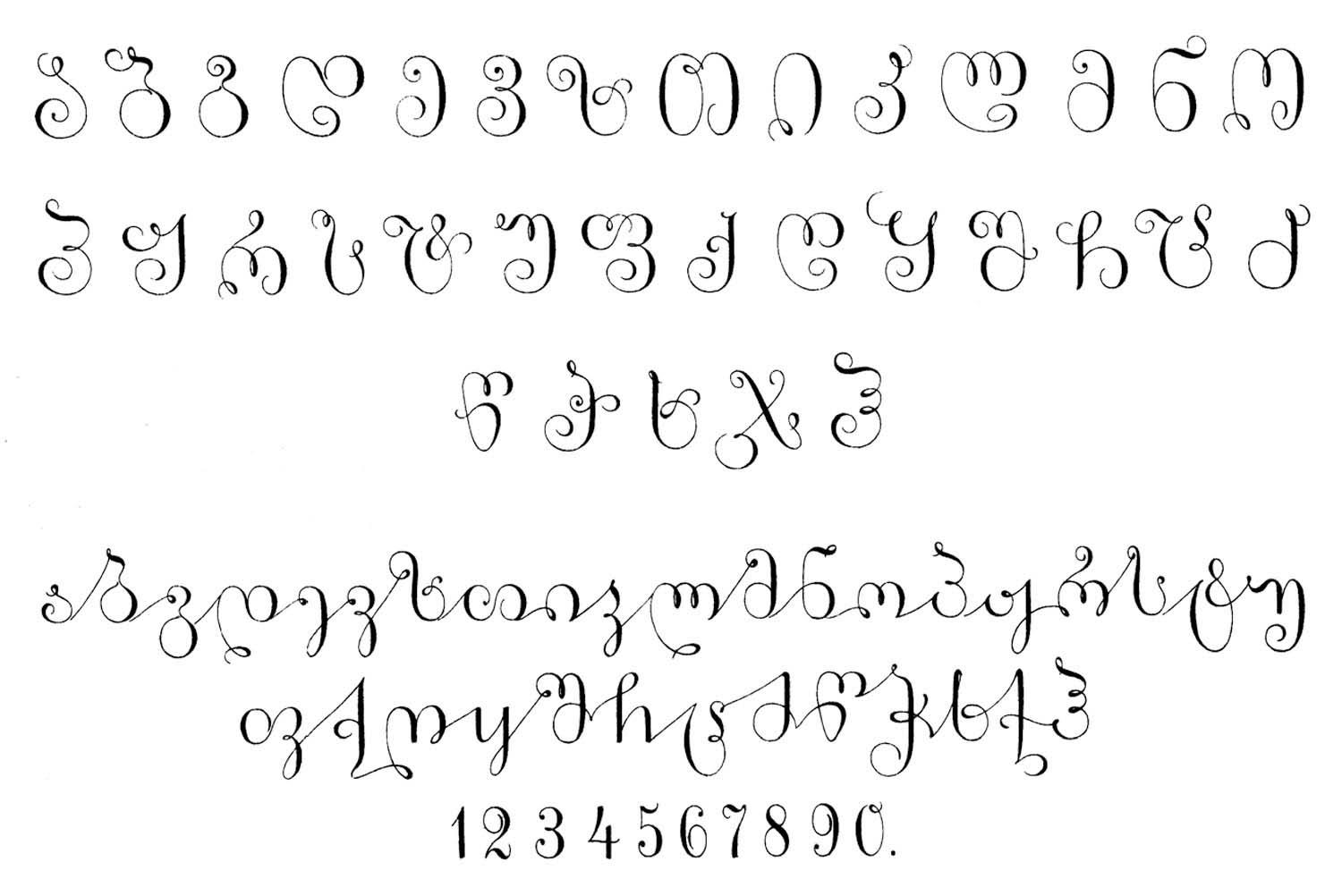

The next stage of development in Georgian type design is connected to St Petersburg. First, several improved versions of the Vakhtangian type were created under the supervision of Baqar Batonishvili (1700–1750), Ioseb Samebeli and Christefore Guramishvili. In 1837, a completely new typeface was cast in the printing house of the Imperial Academy of Sciences, which was developed by the French artist and typeface master De Lafon, based on the handwritten letters of Teimuraz Batonishvili. This typeface is a two-stroke one and is known as ‘Academic’. Iakob Gogebashvili (1840–1912) used its revised version for his children’s and young people’s publications, including his most well-known work Deda Ena (Mother Language), which in turn gave its name to the typeface (Deda Ena). The popular 1888 Kartvelishvili edition of The Knight in the Panther’s Skin (designed by G. Tatishvili, 1838–1911, with illustrations by Mihaly Zichy, 1827–1906) used this typeface.

The next stage is related to the Tergdaleulebi (a revolutionary democratic school of thought in the 1860s and 1870s in Georgia. The term means ‘one who has drunk the waters of Terek’, referring to someone who studied in Russia): on 10 January 1866, the first issue of the newspaper Droeba, printed in the hitherto unknown Mkhedruli typeface, was published in Tbilisi. The author of the typeface was the famous draughtsman, writer and public figure Mikheil Kifiani (1833–1891). In his typeface, he took into account the requirements of polygraphy at that time, created easy-to-read letters using direct outlines, and freed Georgian type design from the influence of handwriting for the first time. In 1864, Stefane Melikishvili, the publisher of Droeba, took the drawings of the new types to Paris and made the matrices there; this font was cast in Vienna, which is why for a long time it was known as ‘Venuri’ (Viennese). In 1950, when the Georgian typography industry was systemised (see below), it began to be called ‘Chveulebrivi’ (ordinary).

In 1882, journalist and public figure Kirile Lortkipanidze (1839–1919) created two new typefaces — ‘Parizuli’ (Parisian) and ‘Lortkipanidze’ — using his own drawings. The first did not correspond to the graphic outline of Georgian letters, while the second was based on the proportions of the Latin type and was inconvenient for reading, so none of them could ultimately be established as the main text types, and they are now used very rarely (mainly on posters, letterheads, etc.). In this period, the first Georgian engraver Grigol Tatishvili also created some title typefaces (‘Chonchkhi’, ‘Egyptian’ and others), but Georgian type design was still developing spontaneously and had a somewhat artisanal character, which is why it lagged significantly behind the Latin or Slavic types of that time.

In 1933, during the time of the Soviet government, the Georgian Type Reform Committee was formed under the leadership of Dimitri Shevardnadze (1885–1937). From a historical point of view, Giorgi Nikoladze also came up with several interesting experimental typefaces; however, unfortunately, they were never completed and therefore were never released.

In 1947, the Georgian Type Committee was created, headed by Beno Gordeziani (1894–1975), the great master of Georgian typography, the most prominent type designer of his time and prolific author of many modern Georgian typefaces. The committee started to explore past heritage, to organise Georgian typography into a system and to adapt it to international standards. With the help of the main printing industry’s experimental type laboratory, the existing typefaces were transformed and completed, Georgian printing was enriched with several new types, created according to modern technological requirements, and the foundation was laid for the systematisation of different variants of the Georgian lettering styles into fonts. In the same period, one of the best text typefaces, ‘Kolkhety’, was created, the author of which was the great champion of Georgian typography, Anton Dumbadze. He created many fonts, as well as heading up the Georgian Type Experimental Laboratory.

Artistic typefaces

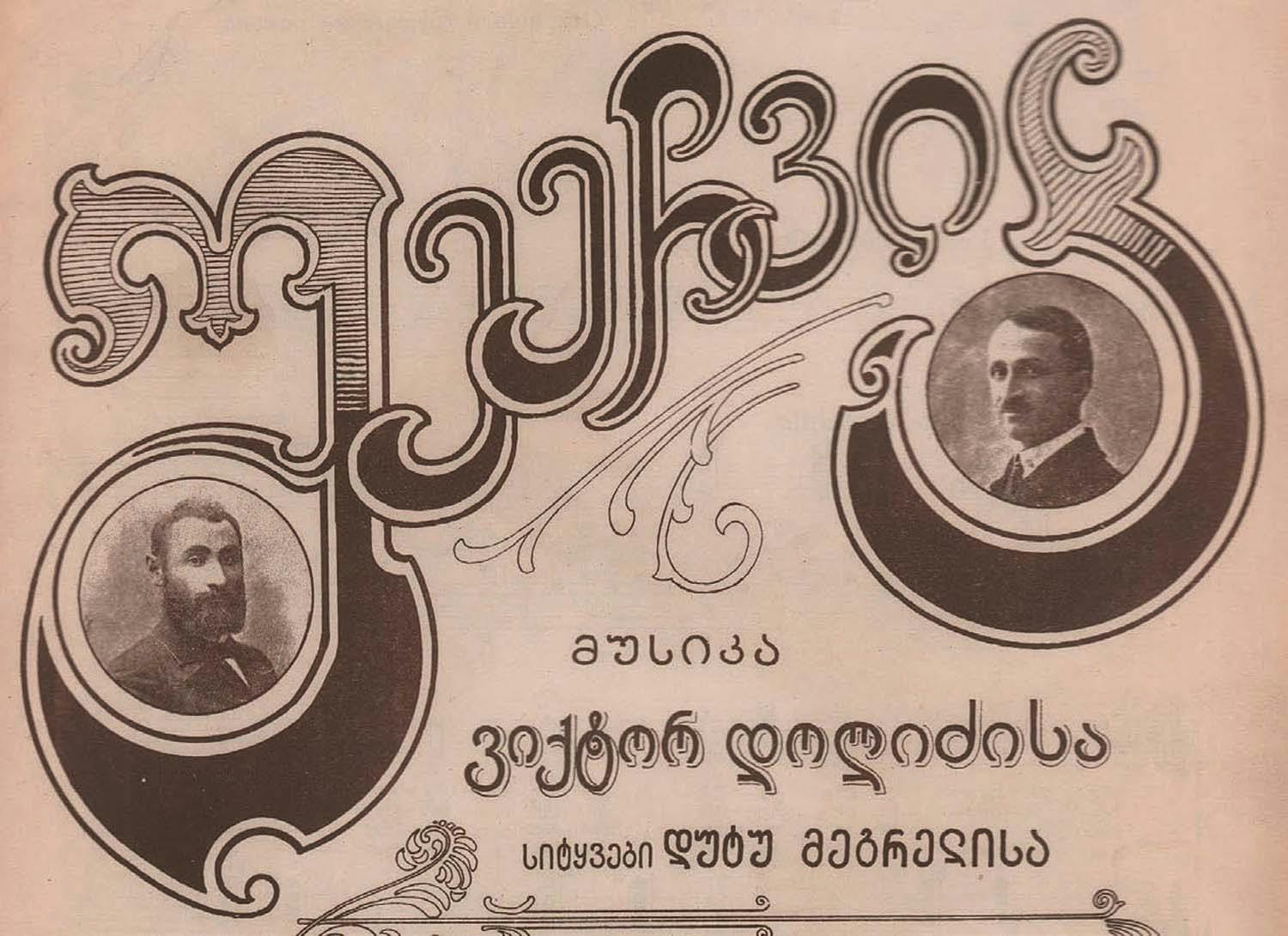

Examples of Georgian artistic typefaces began to appear immediately after the publication of Georgian-language books and the creation of printing types; with the publication of magazines and newspapers, a new field for artistic types emerged. From the second half of the 19th century, more and more attention began to be paid to type design. The increase in the volume of printed products, the quantitative and qualitative changes in literary, political and children’s books, and humorous magazines and newspapers all highlighted the importance of fonts. The emergence of competition led to a focus on the artistic level of publications, which in turn led to the development of the art of type design.

The first artistic typefaces belong to the famous xylographer, font master Grigol Tatishvili. As a result of several decades of hard work, he prepared solid ground for the further development of artistic types and laid the foundation for the interest of the next generation of artists working in the field of type design in the traditions of national art. He was the greatest impetus behind the process in Georgia, which in contrast had taken several centuries and the efforts of hundreds of artists and printers in Europe.

During the short period of independence of the Republic of Georgia (1918–1921), certain font-related processes, similar to other branches of art, were emerging. Georgian fonts began to be used in new fields, exemplified by Georgian banknotes and stamps, and state attributes were created. The authors of these kinds of works (Dimitri Shevardnadze, Iosif Charlemagne) tried to maintain the connection with centuries-old traditions of Georgian art and based the typefaces on its archaic forms. As well as the result of the legacy left by Grigol Tatishvili, header fonts were created under the influence of the fashionable European trend at that time, Jugendstil (modern). This style played a certain role in the updating of the artistic element of type design in Georgia, as in other countries. In Georgia, elements of the modern style can be seen in the artistic types, even after this trend had exhausted its possibilities in Europe.

At the beginning of the 20th century, many Russian avant-garde artists, futurist poets and artists fleeing the Russian revolution, destruction and famine immigrated to Georgia. Together with the Georgian literary and artistic elite, they created a cultural oasis in Tbilisi, declared a ‘fantastic City’ in memoirs and studies. During this period, the printing experiments carried out within the framework of the publishing projects implemented in Tbilisi also had an influence on the development of Georgian typefaces. Following in the footsteps of these trailblazers, a group of young artists, some of whom were futurists (Kirill and Ilia Zdanevich, Beno Gordeziani, Irakli Gamrekeli), tried to revolutionise Georgian type design.

The early 20th century

The founding of the Tbilisi Art Academy in 1922 played an important role in the development of Georgian type design. Among its first teachers were talented drawing masters (Eugene Lansere, Iosif Charlemagne, Henryk Hryniewski), who were well versed in the culture of European type design, while imbued with a deep respect for the traditions of Georgian art. Among the graduates of the Academy were Beno Gordezian, Lado Grigolia, Anton Dumbadze, Lado Kutateladze, Davit Gabashvili, Emir Burjanadze, Shota Kuprashvili, Elene Tvalchrelidze, Davit Dundua, Otar Jishkariani, Teimuraz Kubaneishvili, Otar Varvaridze, Spartak Tsintsadze, Giorgi Gordeladze. They, too, made an important contribution to Georgian artistic types, and Lado Grigolia became one of the founders and theorists of modern Georgian type design.

The Georgian fonts of the 1920s–1930s were influenced by the processes taking place in world art. Constructivism became a kind of successor to the experiments of futurists. In the 1930s, artists tried to create imitations of Chinese, Egyptian, Gothic, Persian and Arabic script using Georgian script. Ioseb (Soso) Gabashvili’s typographic treatment of Firdous’ epic Shahname can be considered one of the best of these attempts, which is in harmony with the miniatures included in the same edition.

By the 1950s, Georgian artistic types already had a clearly formed appearance. The great transformations that took place in the fine arts during this period left a significant mark on the art of typography. Young creators brought with them new ideas, both in terms of book and magazine design, and in graphic design as a whole.

At the same time, artists were becoming interested in creating modern manuscripts of well-known classical and folklore works; Michael Modrekili’s hymns, Ioane Tsurtaveli’s Martyrdom of Shushanik, fairy tales, the Bible, the Gospels and others were all published in the manuscript font. The typefaces were also used in art, paintings and illustrations. Certain type compositions were also generated, including the so-called ‘anbantqeba’, a form of acrostic text/poem, which aims to show the diversity of Georgian fonts and their graphic possibilities.

The late 20th century

From the 1990s, the number of magazines and newspapers began to increase significantly in Georgia, resulting in a great demand for fonts that can be used for newspaper headers and magazine titles. At the same time, the widespread introduction of the computer created a completely new environment, enabling drawing, printing and computer fonts to coexist at the same time. At this stage, cooperation became important, between designers of Georgian fonts and specialists in digital technologies, and it was through such cooperation that the Georgian computer fonts industry, headed by Anton Dumbadze, was formed. He has been leading the Georgian Type Experimental Laboratory since 1973, and is considered the author of many of these fonts.

At the beginning of universal computerisation, many professionals and amateurs became involved in the construction of modern Georgian fonts, including Vano Ramishvili, Elene Failodze, Levan Berdzenishvili, Temur Imnaishvili, Gia Shervashidze, Raul Kuprava, Slava Meskhi, Ilia Boroda (Father Andria) — and many others. Author of Georgian computer fonts and modern text fonts, Bessarion Gugushvili, made a great contribution to this work.

Georgian typography today

In 2001, the Graphic Design Association, together with the Open Society Georgia Foundation, held a Georgian type design competition, as a result of which the stock of Georgian fonts was significantly enriched. In 2016, the same Graphic Design Association published the book Georgian Script and Typography, History, Modernity. In 2017 the German publishing house Buske Verlag (Hamburg) translated the Georgian/English version and then published the German/English edition.

In 2022, with the design and illustrations of Sophia Kintsurashvili and Tamaz Varvaridze, the participation of the famous goldsmith Guji Amashukeli (for the embossed cover) and Georgian calligraphers, the manuscript The Knight in the Panther’s Skin was recreated, the original currently preserved in the art collection of the United Nations. Today, there are many organisations and young designers working in the field of Georgian type design, who are continuing to create new and updated Georgian fonts. In 2023, New Georgian Type has been presented in Tbilisi, renewing interest in type and typography in Georgia.