Modern handwriting: a historical survey

Introduction

‘Writing begins with a basic gesture: a hand holding a pencil traces letters on a page. In the 21st century, very young children can “mark” surfaces, whether intended for this purpose or not, by grasping with care “markers” (pens, felt-tips, pencils) that can be handled without risk, no matter how they hold them: the first jubilant scribbles. However, with a pencil, a metal nib or a felt-tip pen, it will still take them several years to master the writing gestures. Could this learning process be made easier? Should children still be taught to write by hand? In the age of digital messages, is it time for schools to discard the pen for the keyboard?’ 1

Handwriting and how it is taught in primary schools has been the subject of impassioned debate since the advent of mandatory public education in the Western world. Hundreds of articles and books have been devoted to it, presenting, discussing and criticising models and methods of writing. The most recent study published in France, L’école et l’écriture obligatoire, written by the eminent expert Anne-Marie Chartier, provides an impressive historical synthesis and a vivid description of the current situation. Moreover, it is a welcome reminder of the complex scriptural nature of the act of writing itself, made up of choices and power relations:

‘Learning to write means learning a graphic gesture; however, what kind of writing form should one use to learn to write? There have been hundreds of them, as many as there are fonts on our computers. Press articles that oppose cursive and keyboard speak of “the” cursive, as if there were only one, whereas slanted cursive (English Roundhand) is not the upright cursive (Ronde) that has persisted, even after the introduction of print script in nursery school during the interwar years. In Finland, unlike what has been published […], pupils learn to write by hand and with a machine: does this double learning cause problems? Was print script chosen because its letterforms are (almost) those of typographic printing?’ 2

The text you are about to discover is primarily about the many aspects of handwriting, from the late 19th century to the present day. Divided in five sections, it mainly covers Latin writing, but also Cyrillic and Greek; although far from exhaustive, it attempts to give the reader a broad historical perspective and to highlight some recent and contemporary initiatives.

It begins by examining the emergence of new handwriting schemes in Europe and the United States, developed for the sake of public health, or for business.

From slanted to vertical cursive writing

Latin handwriting, in the 19th century, derived from a number of calligraphic styles that had flourished in the previous century. The English Roundhand script (or Copperplate), in particular, was dominating Europe and the United States of America. However, new models began to emerge. They were the result of more pragmatic and expedient approaches, stemming from the intensification of business penmanship that accompanied the Industrial Revolution and the growth of the consumer society.

Some of them, such as the Spencerian script, quickly became established in the second half of the 19th century in the USA. This system was developed by Platt Rogers Spencer, with the aim of combining dexterity, speed and legibility, both in the professional and the domestic spheres. All these cursive models were based on a variable slant, up to 52° for Spencerian and 55° for Copperplate. In addition, these transformations benefited from the simultaneous arrival of new writing tools on the market. Quills and inkwells were slowly superseded by ever better and more efficient fountain pens. The nature and flexibility of the nib was also a determining factor in the quality and contrast variation of handwriting.

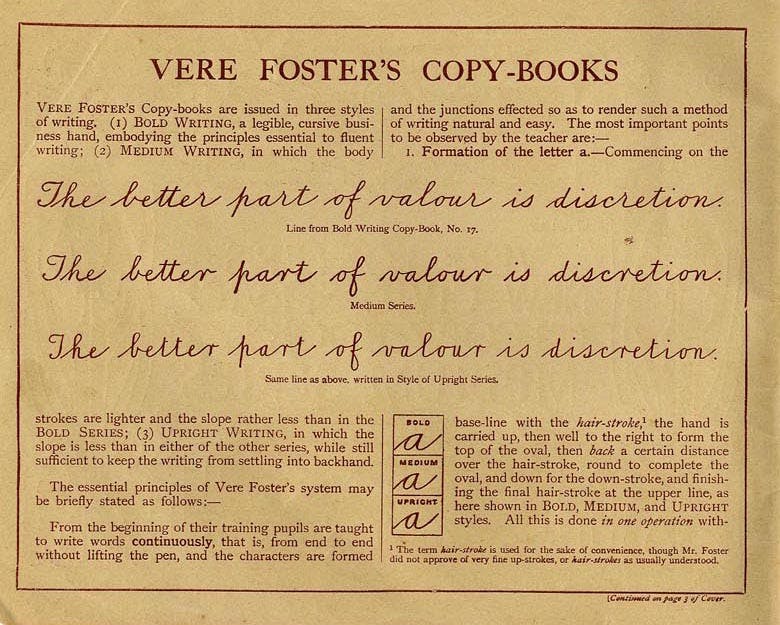

Changes of a different kind began to appear in Europe during the 1860s, challenging the superiority of the well-established calligraphic styles. The first of these was triggered by Vere Foster, an Irish benefactor and publisher of a series of popular copybooks in the English-speaking world until the mid-20th century. Foster, following the recommendations of several teachers and writing masters, brought forward a new, simplified and smoother design named Civil Service script, comprising three models gradually shifting from slanted to upright. 3

This first divergence from traditional slanted cursive writing underlines the possible origin of such changes, this evolution towards verticality being considered a ‘rectification’. It is probable that other models, which were to follow in the wake of Foster’s, were devised in this way. However, others may have been inspired by an already vertical style, such as the Ronde, developed in France during the 17th century and in fact revived during the late 19th century.

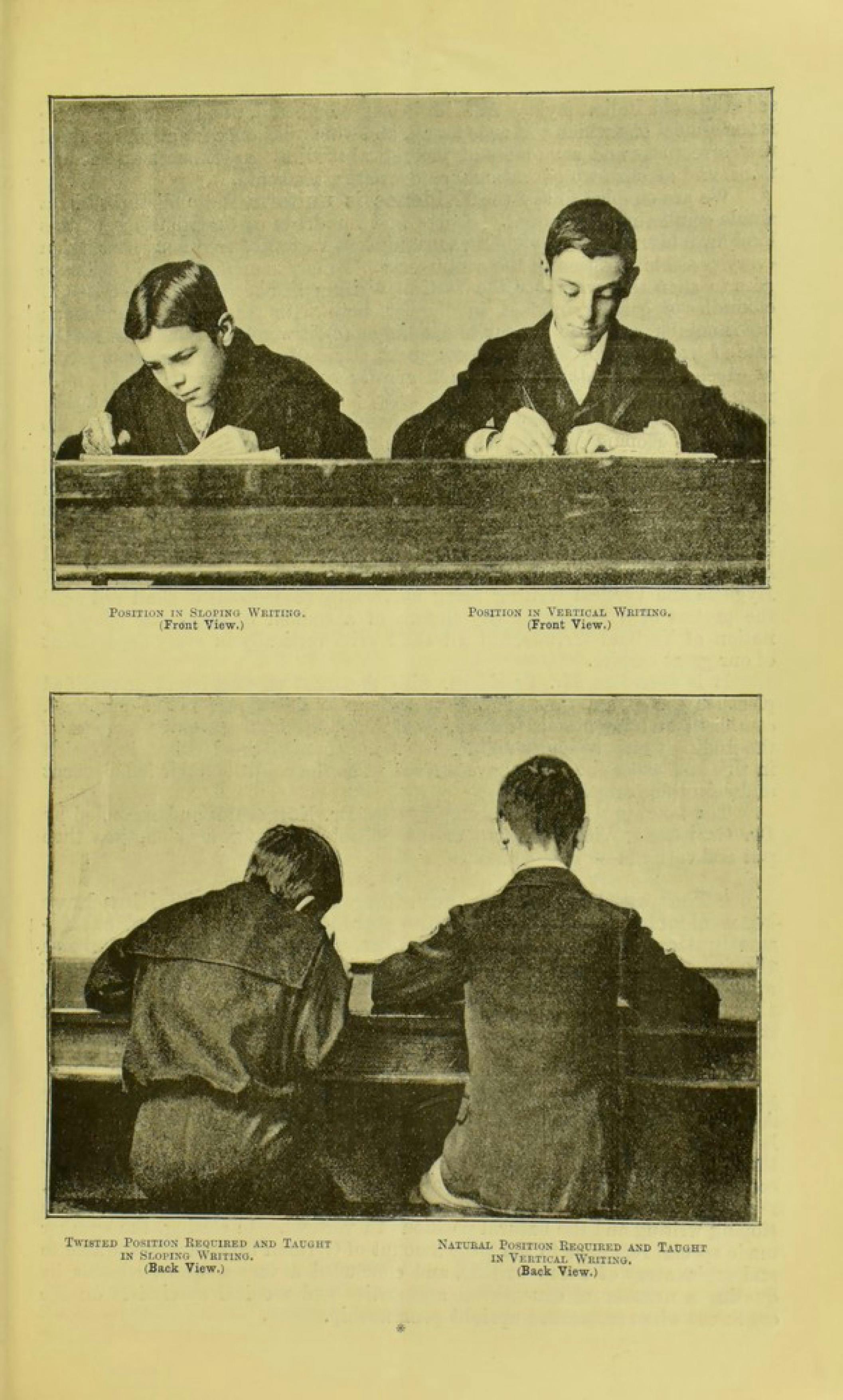

An educational and ‘hygienic’ movement, led by medical experts, burgeoned in the German Empire and in Austria-Hungary in the 1880s.

Its aim was to support the use of vertical writing, in order to prevent certain ophthalmic and orthopaedic disorders caused by the prolonged use of slanted writing. This concern was swiftly echoed in other European countries; around the same time in Great Britain, the professor John Jackson began to define a new model for vertical writing. He attended the Seventh International Congress of Hygiene and Demography in London, in August 1891, and read a paper that was subsequently published, Handwriting in Relation to Hygiene. The final resolution of the congress confidently stated:

‘as the Hygienic advantages of Vertical Writing have been clearly demonstrated and established both by Medical investigation and practical experiment and […] as by its adoption the injurious postures so productive of spinal curvature and short sight are to a very great extent avoided, it is hereby recommended that Upright Penmanship be introduced and generally taught in our elementary and secondary schools.’ 4

Following these recommendations, Austrian and German schools gradually implemented ‘a number of reforms involving not only the slant of the writing, but also the vertical space traversed by the pen, the horizontal length of the copy line, and the distance of the writing line to the copy line’.5

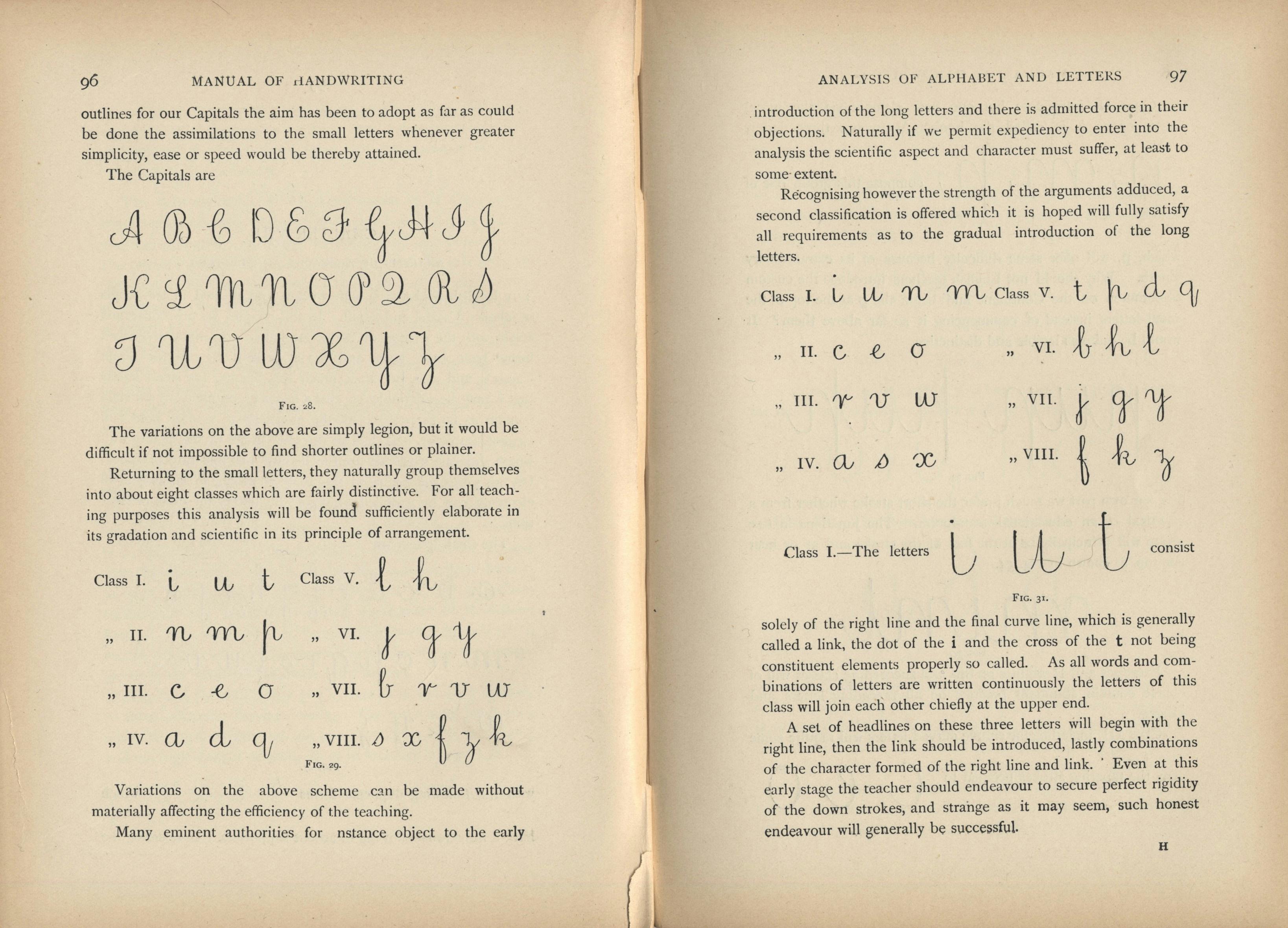

Within a few years, Jackson’s approach and his articles had garnered much interest in Great Britain and the USA, culminating in his main study The Theory and Practice of Handwriting, which was published in London in 1893 and New York in 1894. It is essential to quote a few excerpts from this fundamental text in order to understand the context and the stakes of such a reform movement:

‘Writing is almost as important as speaking, there being no occupation or rank in life into which as a potent factor and as an energising influence writing does not enter. […] Not only is it thus all pervasive throughout civilised society; it rises to even greater prominence and significance in the case of the hundreds of thousands who as secretaries, copyists or clerks follow writing as their profession or business, and derive from it their sole means of subsistence. Such persons are occupied the year round, for from 8 to 16 hours daily, exclusively in clerical work. […] The writing, and not the writer, has always been the supreme consideration in the growth of the art of penmanship. A certain style of writing was deemed or decreed to be essential, the idea of protest was never entertained, and our ancestors had to bend, cringe and twist under the system of bondage thus established. As to Hygienic principles, these have never been associated even in a remote degree with the history of slanting writing that for some two hundred years has flourished amongst us. […] Indeed physiological requirements have not been recognised, much less urged, until within the past few years, and even at the present day but few teachers would be found to spontaneously admit any possible connection between Hygiene and Handwriting. That these Hygienic principles should be an integral part of any system of penmanship whatever, there cannot be the shadow of a doubt, but it may be emphatically stated that the existing style of oblique or slant writing has been elaborated not only independently, but in spite of every physiological demand. […] Vertical Writing is the only specific for these abnormal postures and their train of disastrous consequences. […] The material difference between this Upright or Perpendicular Style and Slanting Writing is in the Direction of the Downstrokes of the letters; in the former being definitely and absolutely Vertical, in the latter indefinitely and variously Sloped or Oblique. It is incredible what a difference this slight and seemingly insignificant alteration in the down strokes makes, and what an effect it exerts upon the writer. When found in conjunction with the minor characteristics of the system, viz. short loops, minimum thickness and continuity, the results are almost magical. […]

In recapitulation, to sum up the essentials of an ideal handwriting that shall fulfil the requirements of Hygiene, the demands of Calligraphic canons and the needs of a mixed community, it has been proved that such writing must be Upright, Continuous, Simple and Plain, with short loops, and a minimum of thickness.

If such a style and system be generally adopted and taught, there will result a generation of writers wonderfully superior to the present generation of scribblers whose penmanship will be a credit instead of a disgrace to their country.’ 6

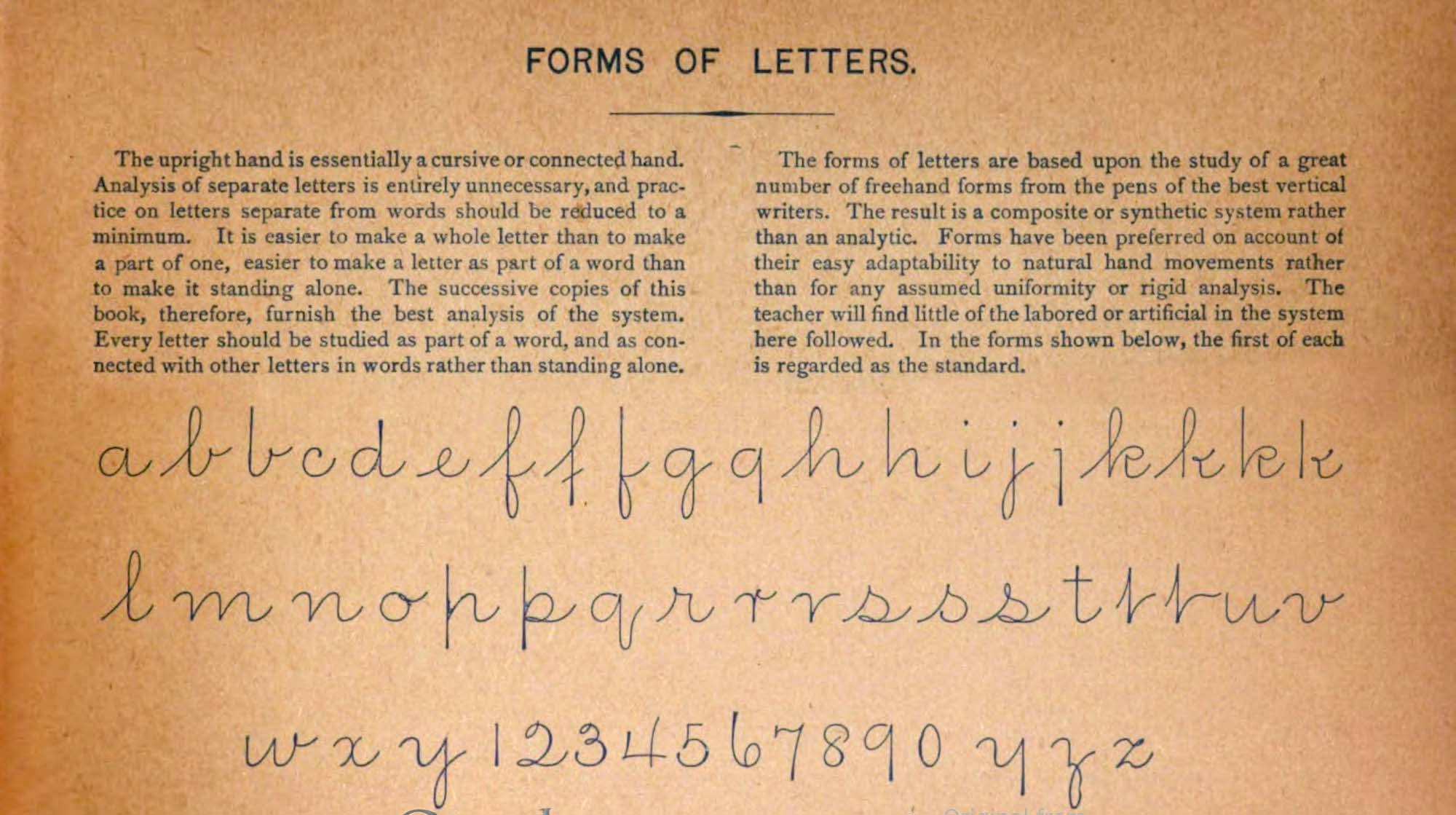

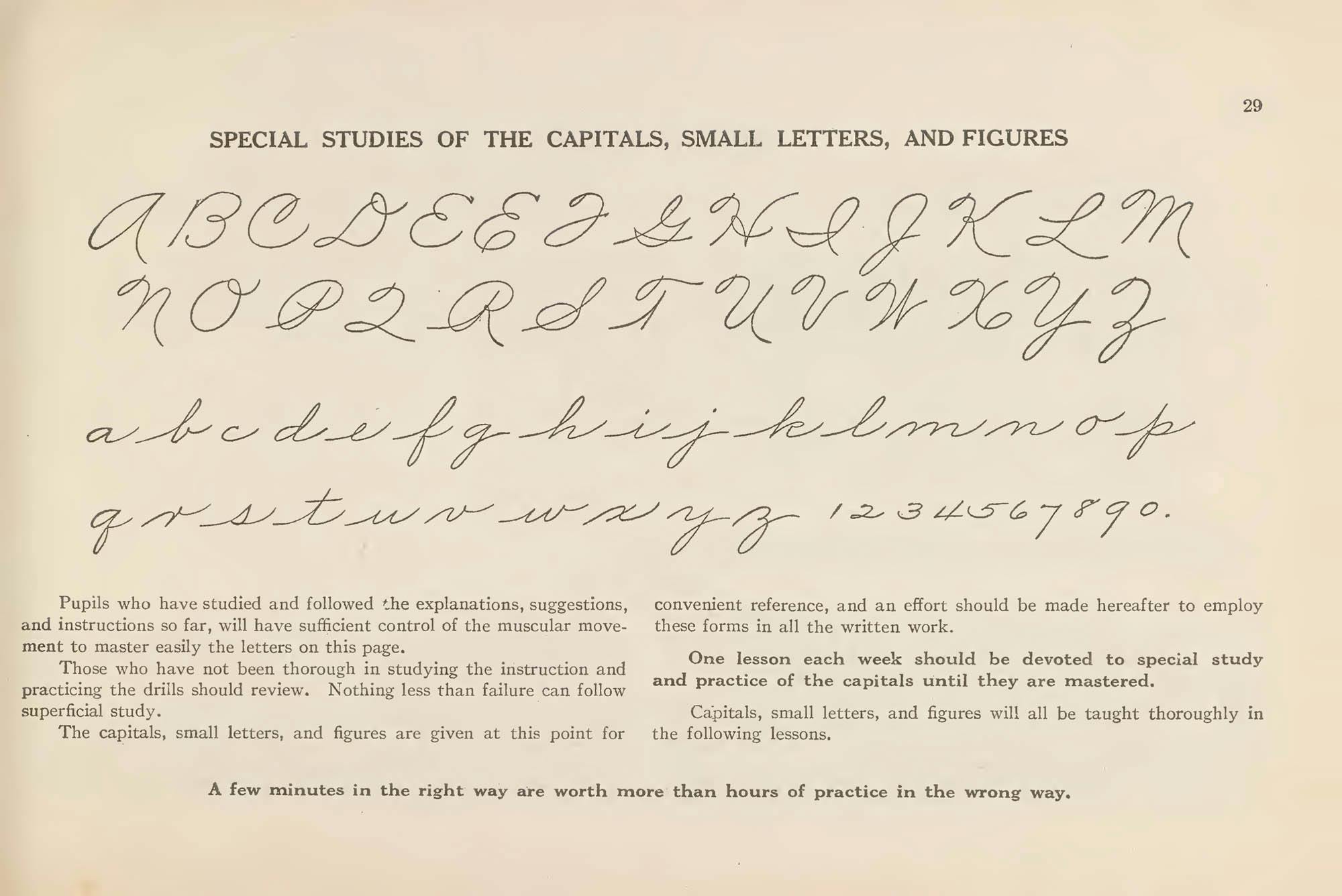

Jackson’s seminal views promoted a new aesthetic of cursive writing, almost breaking completely with previous norms and habits. All of a sudden, a multitude of manuals and models sprung up and were disseminated on the North American continent.

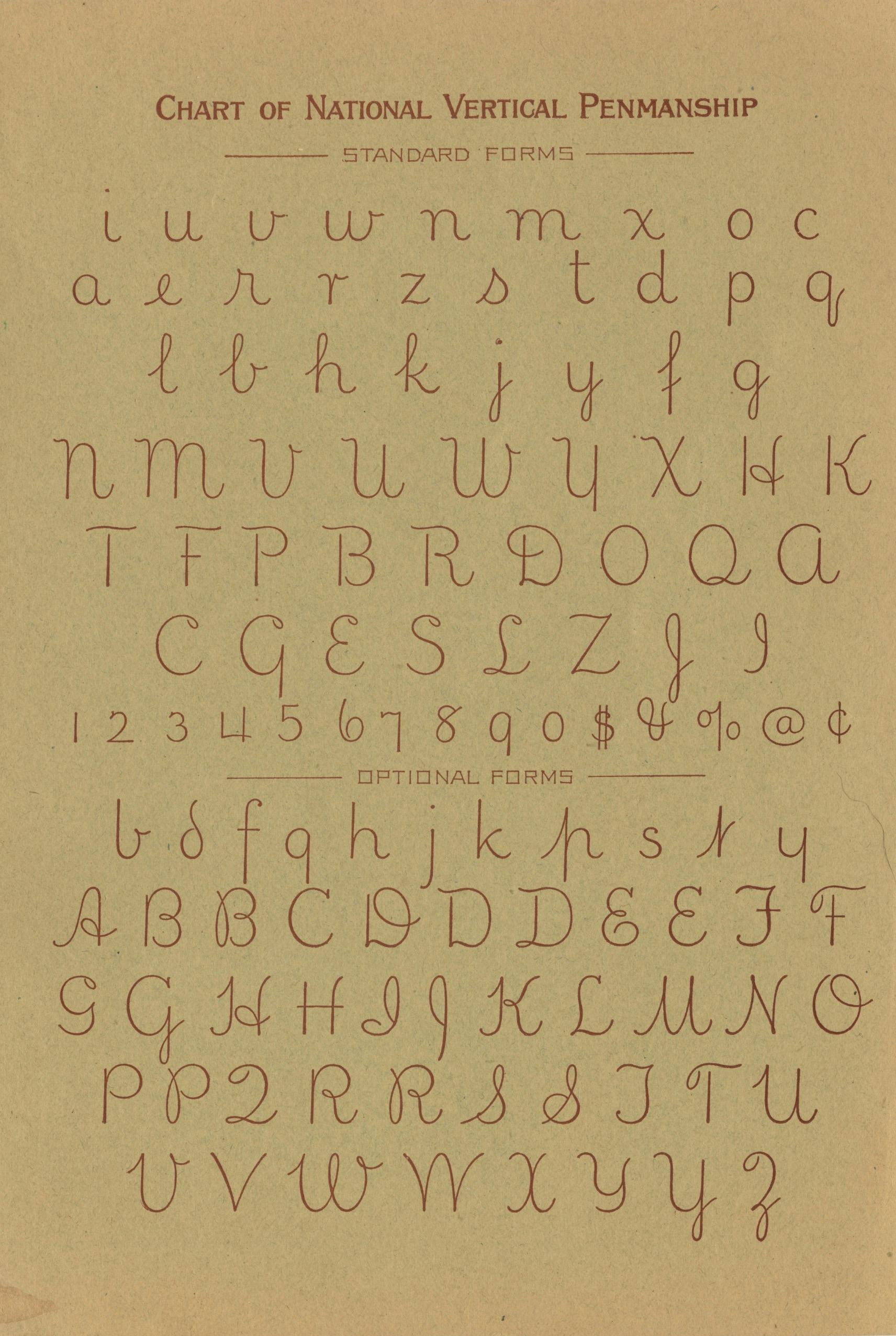

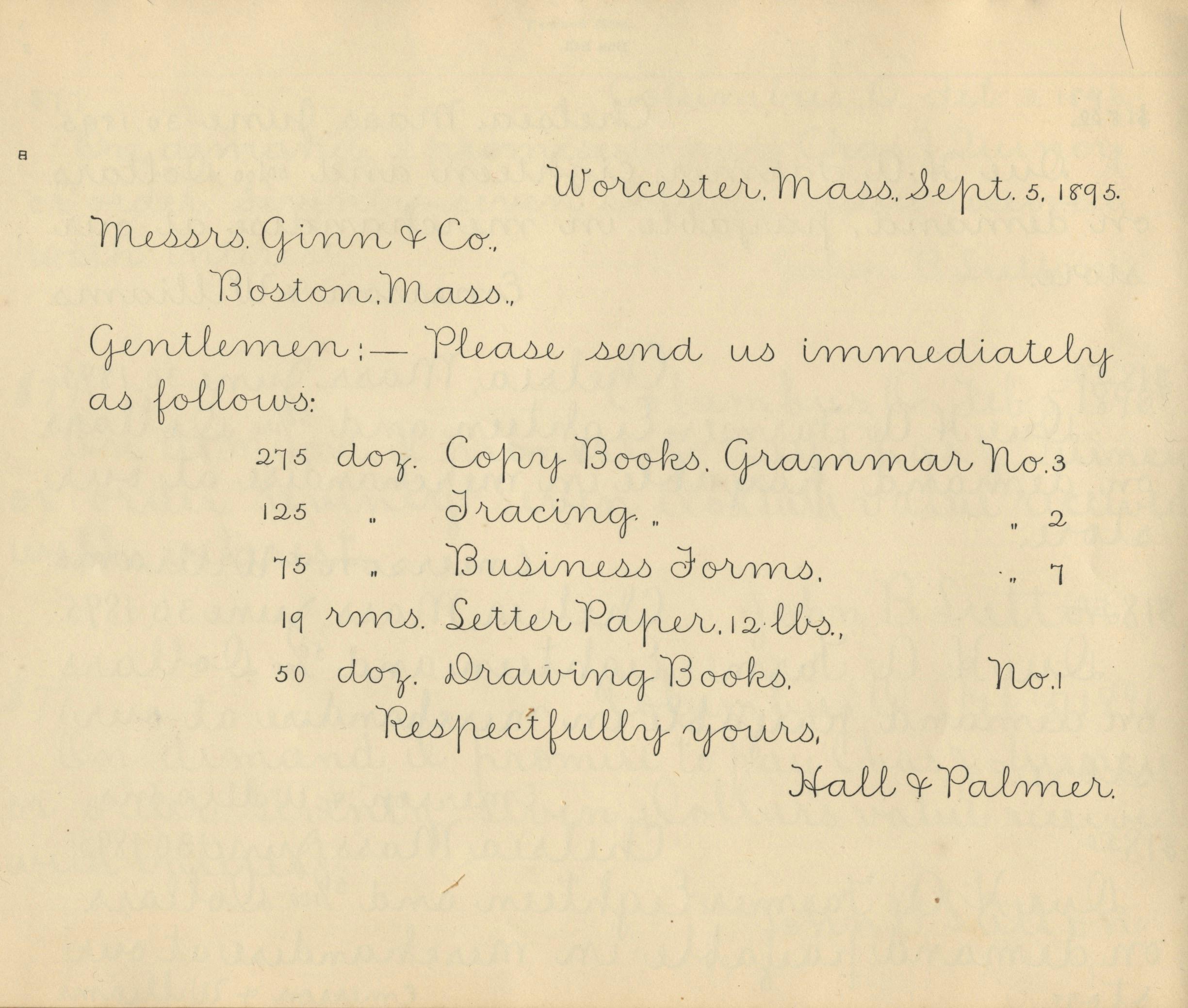

A few examples can be distinguished from this abundant flow. A. S. Barnes & Co.’s Vertical Penmanship series of copybooks (New York, American Book Co., 1898) display a continuous round model. It comprises several alternate letterforms, including flourished capitals. One can also mention, in the same style, A. F. Newlands & R. K. Row’s The Natural System of Vertical Writing (Boston, D.C. Heath, 1896), and Horace W. Shaylor’s Vertical Round Hand model (Boston, Ginn & company, 1897). In this series of copybooks, Shaylor lists the main qualities of his writing system as:

‘legibility – simpler forms, shorter letters, wider spaces; rapidity – less distance travelled, greater freedom of movement; economy – save space and time by omitting superfluous strokes, more words on a line, more lines on a page; beauty – greater uniformity and simplicity; hygiene – position more healthful, strain on eyes spared.’ 7

One additional feature should complete this list: ‘monolinearity’ – low contrast between thick and thin strokes. This was obviously facilitated by the introduction of a wide and diverse range of fountain pens in Europe and the USA.

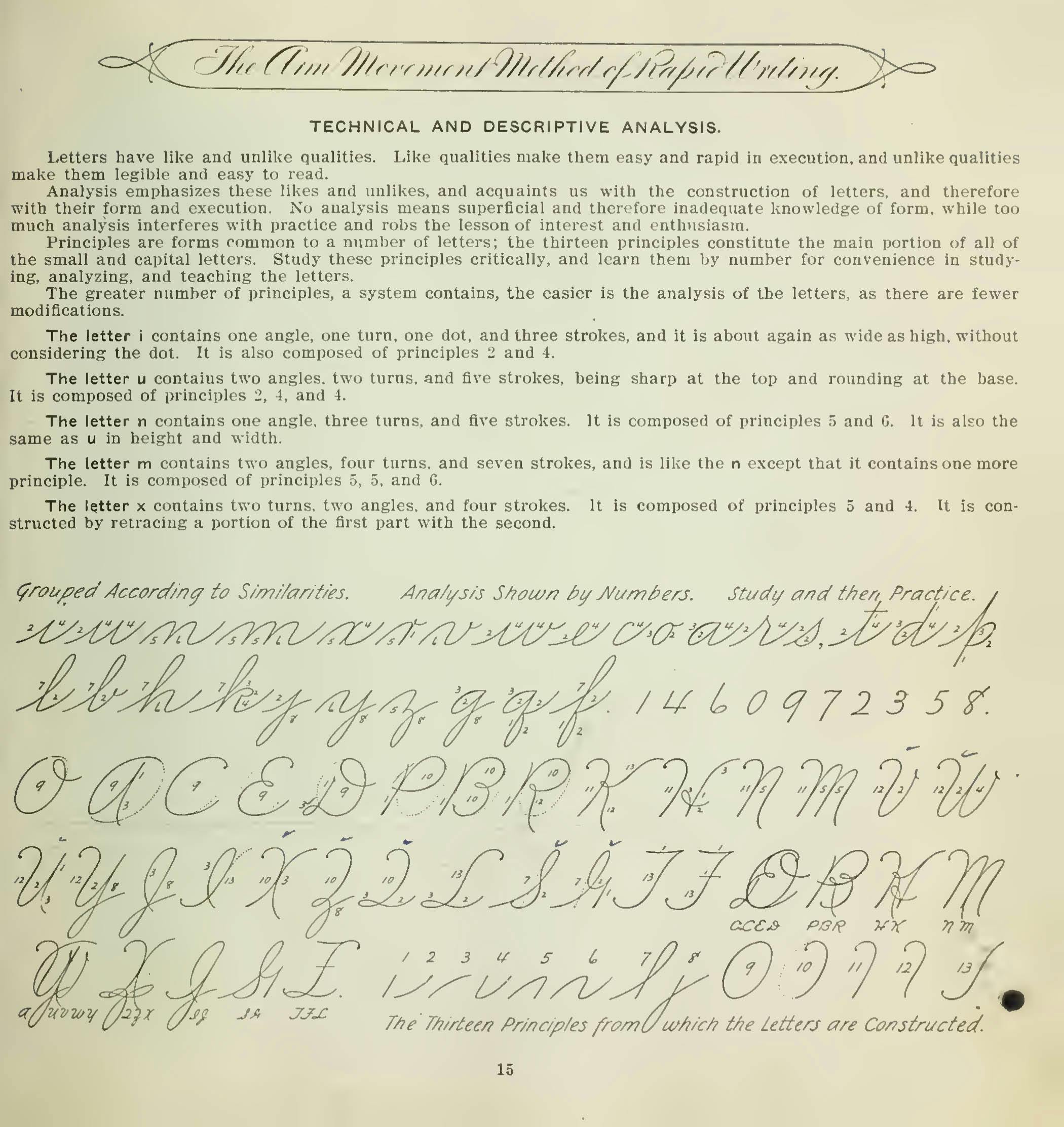

Upright penmanship models started to compete with the widely used Spencerian, which was itself facing the appearance of more innovative slanted cursive designs at the turn of the century. A new method, effectively developed by Austin N. Palmer as a simplification of Spencerian, shared with vertical writing a few hygienic concerns while advocating a different involvement of the body:

‘In the beginning stages of the work, until good position, muscular relaxation, correct and comfortable penholding, and muscular movement as a habit in writing have been acquired, extra practice may be necessary; but the extra time will be saved many times over in all written work later. Muscular movement writing means good, healthful posture, straight spinal columns, eyes far enough away from the paper for safety, and both shoulders of equal height. These features alone should be sufficient to encourage boys and girls to master a physical training system of writing such as is presented in the following pages, remembering that it is impossible to do good muscular movement writing in twisted, unhealthful positions, or with stiff and rigid muscles.

Straight line and oval drills are of no value except as they lead to writing. They are the means through which to gain the muscular control that will enable pupils to master an ideal permanent style of rapid, plain-as-print writing.’ 8

The Palmer Method was soon followed by the quite similar system of Charles P. Zaner and Elmer W. Bloser. While the manual describing the former ignored vertical writing, the latter’s, published in 1904, offers a blunt critique of the method’s partial demise as its momentum had ran out of steam:

‘Writing should be plain and rapid. The business world demands it. Slow writing is out of date, and illegible writing is inexcusable, annoying, and dangerous. […] Copybooks and vertical writing have fostered form at the expense of freedom, and slow, cramped finger movement writing has resulted. Speed and muscular movement theories have fostered freedom at the expense of form, and reckless, scrawling, illegible writing has been the rule. Form without freedom is of little value, and freedom without form is folly. Form and freedom must go hand in hand or failure follows. […]

The teaching of writing to children necessitated something simple and plain. The vertical met that demand, but failed to satisfy or meet the demands of business. It was suited to childhood rather than to commerce, and thereby failed in general usage at the hands of adults.’ 9

These comments also show a clear distinction between the two purposes of teaching writing: first for business employees, and afterwards for the general population. Vertical writing, although discarded in the USA in favour of the new methods of fast and slanted cursive writing, was to fare better in other continents later in the 20th century.

I would like to express my deepest gratitude to Laurence Bedoin, Anya Danilova, Petra Dočekalová, Sandro Fetter, Krista Radoeva, Irina Smirnova, Emilios Theofanous, Irene Vlachou and Annie Vogt for sharing their knowledge and resources.